Virginia Woolf doesn’t write at you; she invites you inside. Her books take the quiet, jittery business of being human — the half-formed memories, the sudden aches of childhood, the private arguments we never voice — and turn them into sentences that feel like walking through someone’s mind. If you’ve ever wondered why modern readers and writers keep circling back to Virginia Woolf, here’s a readable case for stepping into Woolf’s rooms.

A single provocative question: Shakespeare’s sister

Woolf opens one of her most famous essays by asking a what-if: what if William Shakespeare had a sister with equal talent? She imagines this gifted woman shut out of education, marriage-bound, and forced to steal moments for writing between household duties. The point lands hard: talent without social freedom produces silence. That imagined sibling becomes Woolf’s way of arguing that whole traditions of literature never existed simply because women were not given the space — physical, financial, or intellectual — to create.

What “a room of one’s own” really means

Woolf’s demand is twofold: artists need privacy and a basic material independence. By “a room” she means literal space and, by “one’s own,” enough money to live without depending on someone else. Think of it this way: creativity needs both quiet and the freedom to fail. Without them, brilliant potential often dissolves into daily survival. Woolf’s essay still reads like a civil-rights manifesto for the imagination.

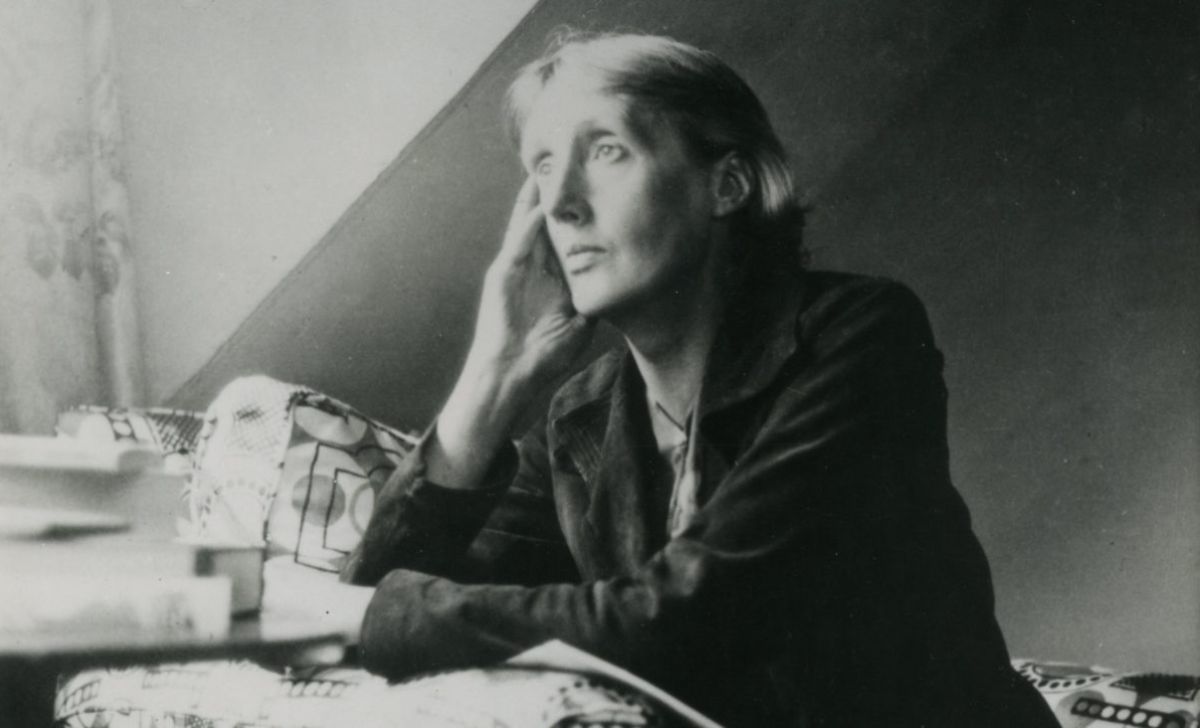

Her life shaped the stories she told

Born Adeline Virginia Stephen in 1882 into a well-off family, Woolf had access to the arts early — and to the losses that would shape her work. Her mother died when Woolf was a teenager; in the following years she lost other close family members, and those deaths triggered severe bouts of depression and hospitalizations. She later married Leonard Woolf and became a central figure in the Bloomsbury Group, a loose circle of writers and artists who pushed the boundaries of taste and form. Those friendships and traumas alike fed her fiction: intimacy, psychic fracture, and the strange persistence of memory recur across her pages.

Modernism as felt experience (not just a style)

Woolf belonged to the modernist wave that includes Joyce and Stein, and she shared their interest in representing consciousness rather than merely reporting events. But where some modernist writing can feel like a technical puzzle, Woolf keeps her experiments human. She uses interior monologue, shifting perspectives, and leaps in time to show how a moment in the present always carries ghosted pasts. If you want prose that tracks how a mind actually moves — distracted, associative, gorgeously elliptical — Woolf is a master teacher.

Reading Woolf through four essential works

Mrs Dalloway: a day like a prism

On the surface, Mrs Dalloway follows Clarissa Dalloway as she plans a party. But Woolf collapses the ordinary into a map of interior lives: a high-society hostess and a traumatized veteran inhabit the same London day, and their private wells of memory reflect and refract each other. Woolf shows how a single day can contain the vastness of a life, with small sensory moments swinging open into huge emotional doors. If you want to feel how memory changes meaning in the blink of an eye, start here. (You’ll probably remember — and maybe recognize — the opening line that anchors the novel.)

To the Lighthouse: time as tide

To the Lighthouse often reads like a family album under a magnifying glass. A dinner, a lost necklace, a seaside house — these modest facts prompt intimate revelations. The novel’s famous “Time Passes” section compresses years into a handful of pages, turning a house into a vessel that ages while human lives move in and out. Imagine a timelapse of domestic life: the smallest gestures accumulate into history. Woolf asks how art can capture those slow, almost invisible erosions.

The Waves: six voices, one ocean

In The Waves Woolf pushes voice to a new limit: six characters speak in curving, interlaced soliloquies that sometimes dissolve into a single communal voice. The book feels like listening to a choir where individual melodies blur into a single, strange song about identity, belonging, and change. If you’re curious about how narrative can become musical, this is Woolf finely tuned.

Orlando: a biography that bends time and gender

Orlando reads like a biographical prank — a person lives for three centuries and changes sex along the way. The book slips between satire, fantasy, and earnest meditation on identity. Its playful form makes serious points about gender, creativity, and historical constraint. Read it for the pleasure of seeing a life refuse to be pinned down.

Why Woolf still matters to readers now

Woolf insists that inner life deserves to be heard. Her writing trains you to notice how a smell, a passing phrase, or a city corner can reroute a whole mind. That attentiveness makes her great for anyone who wants literature that’s emotionally precise and stylistically adventurous. She also offers a sustained critique of exclusion — reminding us that who gets to write history shapes what history becomes.

A reader’s starter pack (where to begin)

If you want a guided route:

- Start with the essay A Room of One’s Own for the clearest statement of her ideas about art and freedom.

- Move to Mrs Dalloway to feel her narrative empathy in full swing.

- Try To the Lighthouse if you like psychological depth and lyrical time shifts.

- Read Orlando for a lighter, boundary-bending ride.

A final note — the writer and the person

Woolf’s life contained bright friendships and terrible sorrow; she struggled with mental illness and ended her life at 59. That fact casts a long shadow, but it doesn’t reduce her work to tragedy. Her fiction and essays repeatedly return to the possibility of connection: when minds touch one another in language, something like consolation occurs. If you read Woolf closely, you’ll find sentences that make private experience public — and, in doing so, make us a little less alone.