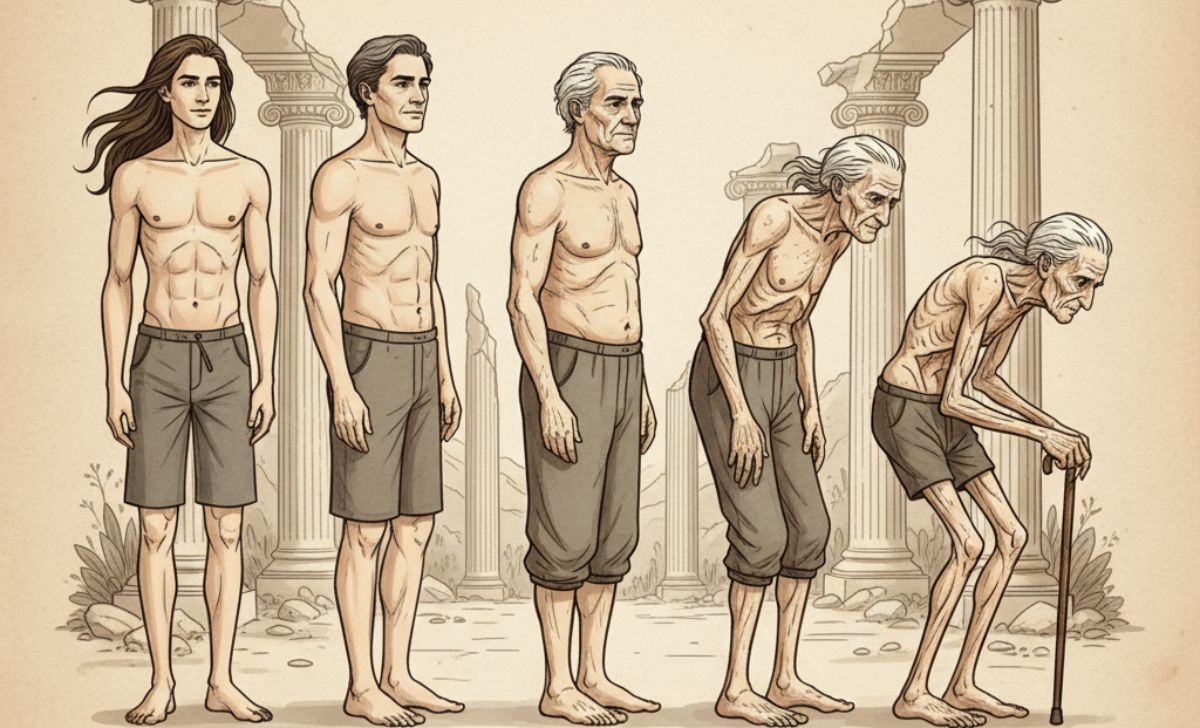

What makes our bodies age as the years pass? It’s a question that has fascinated scientists and philosophers alike for centuries. As time moves forward, our cells slow their renewal, our DNA accumulates tiny damages, and our organs lose efficiency. Aging is not caused by a single factor but by a complex interplay of biology, lifestyle, and environment that gradually reshapes how our bodies function—reminding us that time, though invisible, leaves its mark on every part of us.

The Cellular Foundation of Aging

At the most fundamental level, aging begins within our cells. Cellular senescence, a state where cells permanently lose their ability to divide, drives many age-related changes throughout the body. Scientists identify this process as triggered by several key factors that accumulate damage over time.

Telomere Shortening represents one of the most significant cellular aging mechanisms. These protective DNA caps at chromosome ends shorten with each cell division, functioning as biological clocks. When telomeres become critically short, cells enter senescence or undergo programmed death. Research demonstrates that telomeric DNA damage creates irreparable lesions that persist throughout aging, making these structures particularly vulnerable targets for age-related deterioration.

DNA Damage and Genomic Instability accelerate aging through accumulated mutations and repair defects. The body’s DNA repair mechanisms become less efficient over time, allowing damage to accumulate faster than it can be corrected. This creates a cascade of cellular dysfunction that spreads throughout tissues and organs.

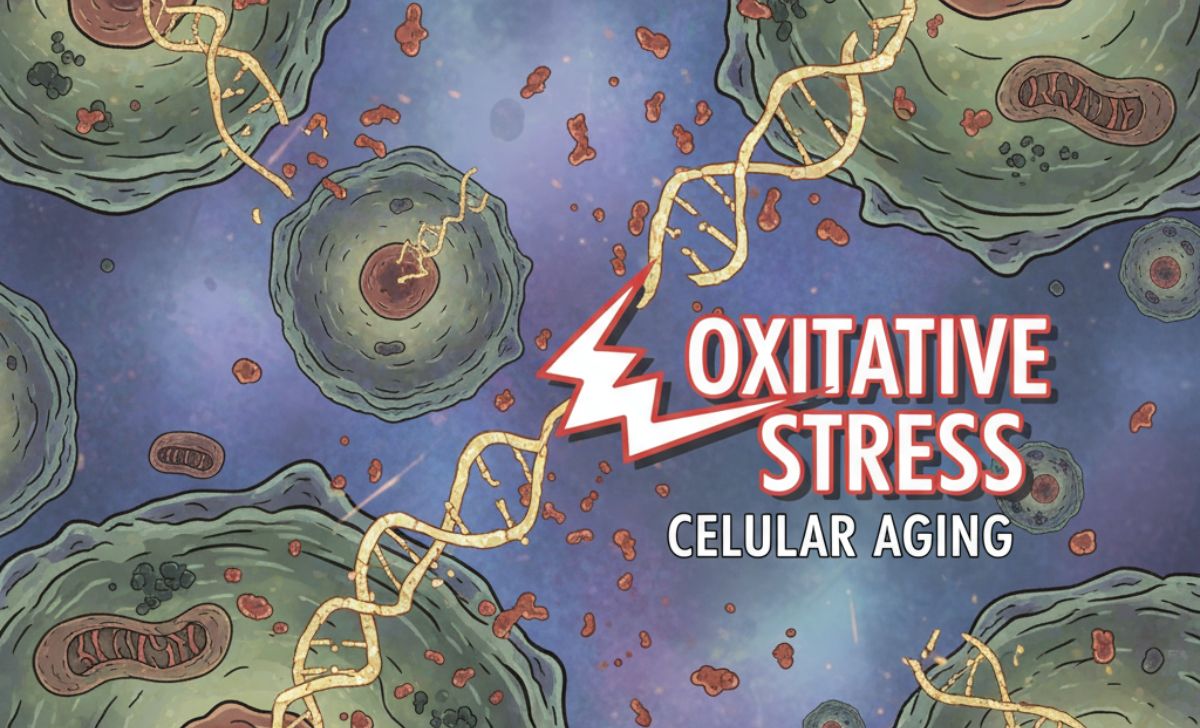

Mitochondrial Dysfunction compounds cellular aging by disrupting energy production. These cellular powerhouses become increasingly damaged with age, producing fewer energy molecules while generating more harmful reactive oxygen species. This oxidative damage creates a self-reinforcing cycle that accelerates cellular deterioration.

The Molecular Mechanisms Behind Age-Related Changes

Protein Production Decline fundamentally alters how cells function as we age. The body’s ability to synthesize the proteins necessary for muscle growth, repair, and maintenance decreases significantly over time. This protein synthesis decline directly contributes to muscle mass loss and reduced cellular repair capacity.

Oxidative Stress and Free Radical Damage accelerate aging by overwhelming the body’s antioxidant defenses. Daily metabolic processes generate unstable molecules called free radicals, while external factors like UV radiation and pollution create additional oxidative stress. When these reactive molecules exceed the body’s neutralizing capacity, they damage cellular structures and DNA.

Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation, termed “inflammaging,” characterizes the aging process. Unlike acute inflammation that resolves after injury, this persistent inflammatory state damages tissues continuously and contributes to age-related diseases. The accumulation of senescent cells releasing inflammatory signals perpetuates this damaging cycle.

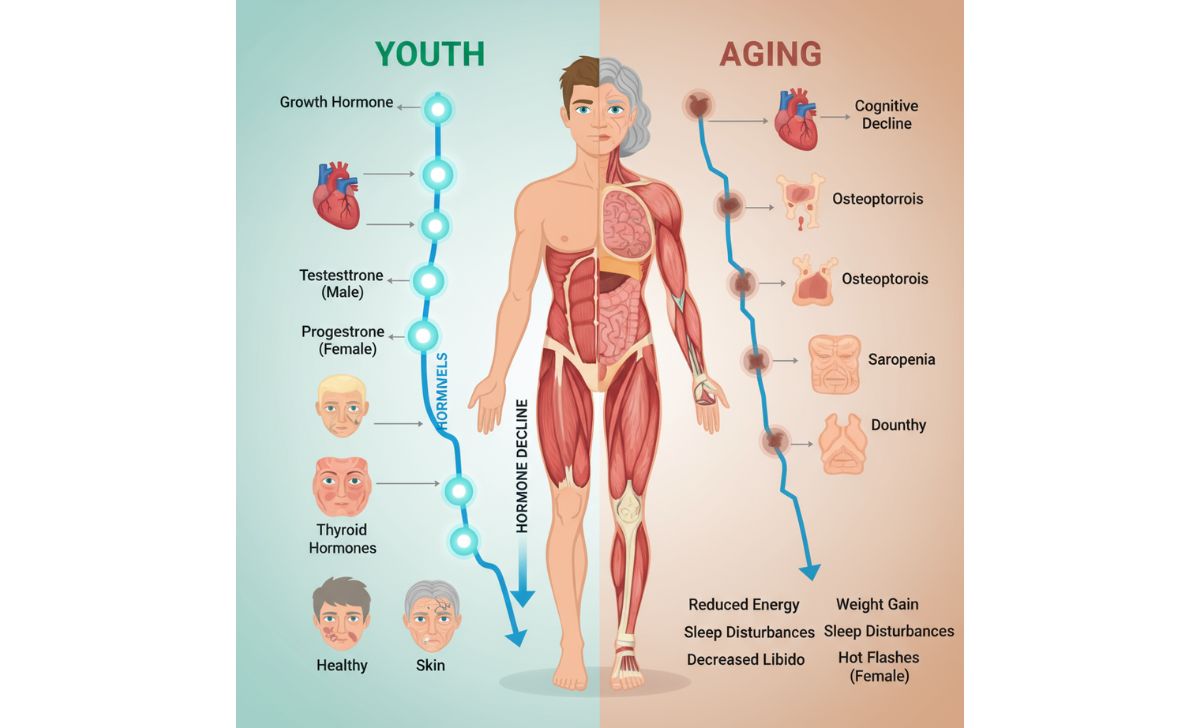

Hormonal Changes That Drive Aging

The endocrine system undergoes dramatic changes with age, contributing significantly to the aging process. These hormonal shifts affect multiple body systems simultaneously.

Andropause brings gradual testosterone decline beginning around ages 20-30 in men. This decrease affects muscle mass, bone density, energy levels, and overall metabolic function. Women also experience testosterone decline, though at lower baseline levels.

Adrenopause involves reduced production of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its sulfate form. These hormones play crucial roles in immune function, stress response, and overall vitality.

Somatopause describes the declining production of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). These hormones regulate muscle mass, bone density, and cellular repair processes throughout the body.

Menopause represents the most dramatic hormonal transition, occurring around age 50 when estrogen and progesterone production ceases. Beyond reproductive changes, this transition affects cardiovascular health, bone density, and overall metabolic function.

The Breakdown of Body Systems

Musculoskeletal System Deterioration

Sarcopenia, the age-related loss of muscle mass and strength, begins as early as the fourth decade of life. Up to 50% of muscle mass may be lost by the eighth decade, with profound consequences for mobility and independence. This occurs through multiple mechanisms including decreased protein synthesis, hormonal changes, reduced neuromuscular junction function, and chronic inflammation.

The loss primarily affects fast-twitch muscle fibers, while infiltration of fibrous and fatty tissue replaces functional muscle. Satellite cells, which repair and regenerate muscle tissue, also decline in number and function with age.

Cardiovascular System Changes

The cardiovascular system undergoes significant structural and functional modifications with aging. Heart walls thicken and become stiffer, reducing the heart’s filling capacity and potentially leading to heart failure. The left ventricle may enlarge, but its functional capacity often decreases.

Blood vessels lose elasticity as arterial walls thicken and elastic tissue degrades. This stiffening increases blood pressure and forces the heart to work harder. Baroreceptors, which help regulate blood pressure, become less sensitive, contributing to orthostatic hypotension in older adults.

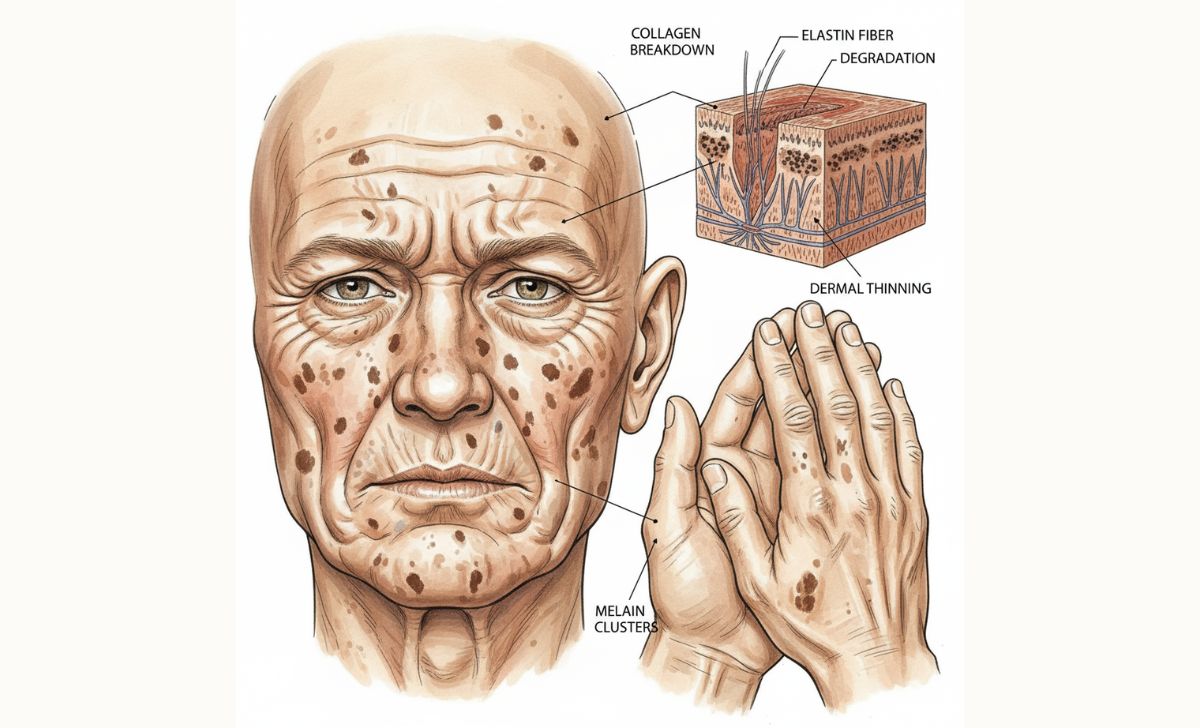

Skin and Connective Tissue Aging

Skin aging occurs through both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Collagen and elastin production decline approximately 1% annually, leading to wrinkles, sagging, and reduced skin elasticity. The skin becomes thinner, drier, and more fragile as cell turnover slows and natural oil production decreases.

Photoaging from UV radiation represents the primary extrinsic aging factor. Sun exposure damages collagen fibers and triggers abnormal elastin production, creating deeply wrinkled, leathery skin texture. This process accelerates the natural aging timeline significantly.

Nervous System Deterioration

Brain aging involves complex changes affecting cognitive function, motor control, and sensory processing. Synaptic connections weaken, myelinated fibers connecting brain regions deteriorate, and higher-order integration becomes less efficient.

Neurodegeneration occurs through accumulation of damaged proteins, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular senescence. While neuronal loss is minimal in healthy aging, changes in synaptic function and neurotransmitter balance significantly impact cognitive performance.

Immune System Decline

Immunosenescence describes the age-related deterioration of immune function. The thymus gland involutes after puberty, reducing naive T cell production while increasing memory T cells. This shift impairs responses to new pathogens and reduces vaccine efficacy in older adults.

Chronic inflammation associated with immunosenescence creates an immunosuppressive environment that further compromises immune responses. The accumulation of senescent cells that escape immune clearance perpetuates this inflammatory state.

The Interconnected Nature of Aging

Aging represents a complex interplay of multiple biological systems rather than isolated changes. Cellular senescence creates inflammatory signals that accelerate aging in neighboring cells and tissues. Hormonal changes affect multiple organ systems simultaneously. Cardiovascular changes impact nutrient delivery to all tissues, while immune dysfunction allows senescent cells to accumulate unchecked.

Protein homeostasis loss affects cellular function across all systems. The accumulation of damaged proteins and reduced quality control mechanisms contribute to aging phenotypes throughout the body.

Autophagy decline impairs cellular recycling and repair processes. This cellular housekeeping system becomes less efficient with age, allowing damaged components to accumulate and interfere with normal function.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors

While genetic factors influence aging rates, environmental and lifestyle choices significantly impact the aging process. Regular exercise, proper nutrition, adequate sleep, stress management, and sun protection can slow many aging mechanisms.

Physical activity maintains muscle mass, cardiovascular function, and cognitive abilities while reducing chronic inflammation. Nutritional factors affect cellular repair processes, oxidative stress levels, and metabolic function throughout life.

Implications for Healthy Aging

Understanding aging mechanisms provides insight into potential interventions and lifestyle modifications that may slow the aging process. While aging remains inevitable, research suggests that many age-related changes can be delayed or mitigated through targeted approaches addressing the underlying biological mechanisms.

The interconnected nature of aging systems means that interventions targeting one mechanism may have beneficial effects across multiple systems. This systems-level understanding of aging opens new possibilities for promoting healthy longevity and maintaining function throughout the human lifespan.