- The human body contains two main types of sweat glands: eccrine and apocrine glands.

- When apocrine sweat interacts with bacteria on the skin, it produces the characteristic body odor often associated with …

- As sweat evaporates from the skin, it dissipates heat, keeping internal organs safe and body temperature stable.

- Sweating becomes the body’s most efficient method to cool down.

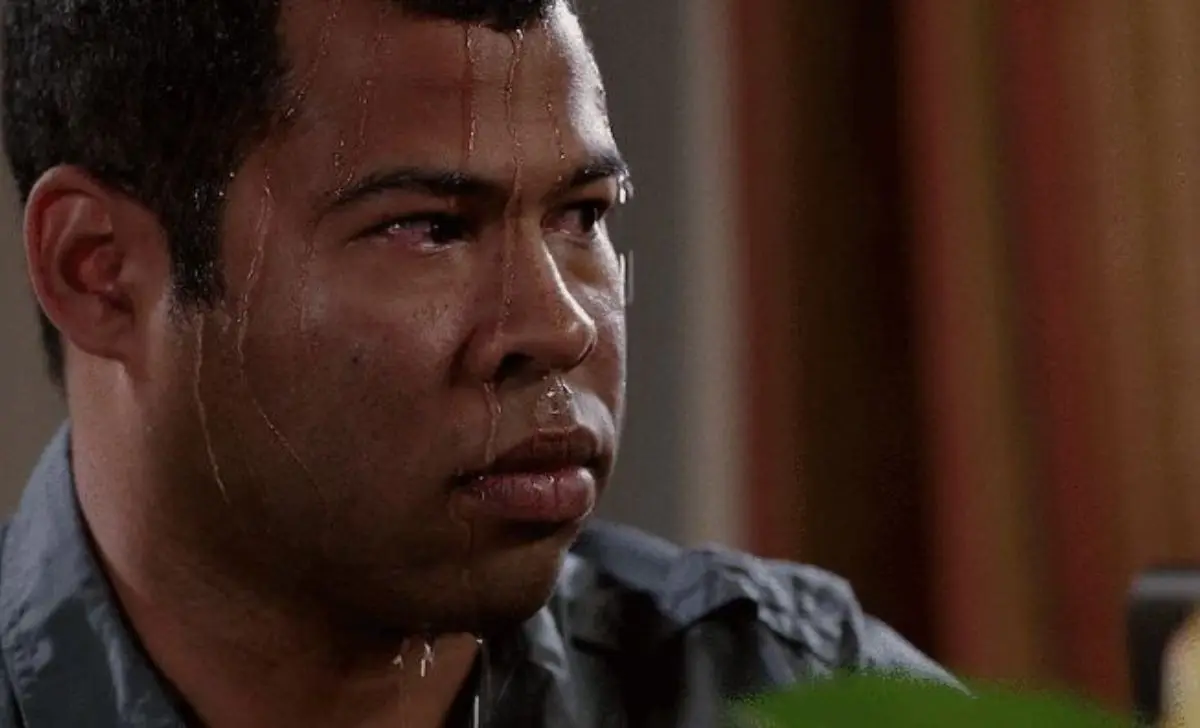

- Emotions such as fear, anxiety, embarrassment, and excitement can also induce sweating, known as emotional sweating…

- Spicy foods, caffeine, and alcohol stimulate nerve endings that control sweat glands, leading to gustatory sweating…

Sweating is one of those everyday processes that most of us rarely think about—until it becomes inconvenient. Whether you’re drenched after a gym session, feeling clammy before a big presentation, or perspiring on a hot summer day, sweating is a natural and vital biological response. It is the body’s built-in cooling mechanism, a sophisticated process designed to maintain internal balance and protect us from overheating. But there’s more to it than just perspiration and odor. Understanding why our body sweats, what causes sweating, and its physiological importance reveals how essential this process is to our survival and overall health.

The Science Behind Sweating

Sweating, or perspiration, occurs when glands in the skin secrete a fluid primarily made up of water and salts, known as sweat. This fluid evaporates from the skin’s surface, carrying heat away from the body and lowering internal temperature. The human body maintains a narrow range of internal temperature, typically around 37°C (98.6°F), and sweating is one of the key mechanisms for regulating this temperature.

The process begins in the thermoregulatory center of the brain, located in the hypothalamus. When this center detects a rise in body temperature—whether due to environmental heat, physical exertion, or emotional stress—it sends signals through the autonomic nervous system to activate sweat glands across the skin. The glands then produce sweat, which exits through pores, spreads over the skin, and cools the body when it evaporates.

This intricate feedback system ensures that the body doesn’t overheat, even during intense physical activity or in extreme temperatures.

Types of Sweat Glands and Their Functions

The human body contains two main types of sweat glands: eccrine and apocrine glands. Though both produce sweat, they serve different functions and respond to distinct triggers.

- Eccrine glands: These are the most common and widespread sweat glands, numbering between two to four million in the human body. They are particularly abundant on the palms, soles, forehead, and chest. Eccrine glands secrete a watery, odorless sweat composed mostly of water, sodium, and trace amounts of potassium and chloride. Their primary role is thermoregulation—cooling the body when temperatures rise or during physical exertion.

- Apocrine glands: Found mainly in areas with abundant hair follicles, such as the armpits and groin, these glands produce a thicker, milky fluid that contains proteins and fatty acids. Unlike eccrine glands, apocrine glands become active during puberty and are primarily triggered by stress, emotion, or hormonal changes rather than temperature. When apocrine sweat interacts with bacteria on the skin, it produces the characteristic body odor often associated with sweating.

Both types of glands play distinct yet complementary roles in maintaining the body’s internal balance and responding to environmental or emotional changes.

Why the Body Sweats: Core Reasons and Triggers

Sweating serves multiple vital purposes, from regulating temperature to expressing emotions. Here are the primary reasons our bodies engage in this process:

1. Thermoregulation

The most fundamental reason we sweat is thermoregulation—the body’s effort to maintain a constant internal temperature. During physical activity, our muscles generate heat as they burn energy. Similarly, when external temperatures rise, heat accumulates in the body. To prevent overheating, the hypothalamus triggers eccrine glands to release sweat. As sweat evaporates from the skin, it dissipates heat, keeping internal organs safe and body temperature stable.

2. Physical Exertion

When exercising, the body’s demand for energy increases, leading to greater heat production. Sweating becomes the body’s most efficient method to cool down. Athletes and physically active individuals often develop a more rapid and profuse sweating response because their bodies adapt to regulate heat more effectively over time.

3. Emotional and Psychological Stress

Emotions such as fear, anxiety, embarrassment, and excitement can also induce sweating, known as emotional sweating. This is mainly regulated by apocrine glands and is a response to activation of the sympathetic nervous system—the same system that triggers the “fight or flight” reaction. This type of sweating typically appears on palms, soles, and underarms. It helps improve grip and can be a leftover survival mechanism from our evolutionary past, where sweating on the palms helped early humans handle tools or climb better under stress.

4. Hormonal Fluctuations

Hormones can significantly impact sweating. For instance, during menopause, drops in estrogen levels can cause the hypothalamus to misinterpret body temperature, leading to sudden sweating episodes known as hot flashes. Similarly, hormonal changes during puberty can increase apocrine gland activity, explaining why teenagers often experience more noticeable body odor and sweating.

5. Illness or Fever

When infected with bacteria or viruses, the body raises its temperature to fight off pathogens. Sweating during a fever is a sign that the body is attempting to cool itself down after the fever subsides, restoring the normal thermal balance.

6. Dietary and Metabolic Influences

Certain foods and drinks can also trigger sweating. Spicy foods, caffeine, and alcohol stimulate nerve endings that control sweat glands, leading to gustatory sweating. Metabolically, individuals with faster metabolisms may produce more heat, requiring more frequent sweating to maintain thermal balance.

What Sweat Is Made Of

Sweat might seem like simple water, but it contains a complex mix of components that varies depending on factors such as hydration, diet, and temperature. It is typically made up of:

- 98–99% water

- 0.2–1% salts, primarily sodium and chloride

- Trace amounts of potassium, calcium, magnesium

- Small quantities of urea, ammonia, lactic acid, and other metabolic byproducts

These electrolytes are essential for maintaining cellular function, muscle contractions, and nerve signaling. However, excessive sweating can lead to electrolyte imbalances, particularly in hot climates or during intense physical exertion without proper hydration.

When Sweating Becomes a Problem

While sweating is vital for survival, too much or too little of it can indicate underlying health concerns.

Hyperhidrosis

This condition involves excessive sweating beyond what is necessary for temperature regulation. It can occur in specific areas like the palms, soles, and underarms (primary hyperhidrosis) or as a result of medical conditions such as thyroid disorders, diabetes, or medication side effects (secondary hyperhidrosis). Though not dangerous, it can be socially embarrassing and affect quality of life. Treatments include antiperspirants, medications that block sweat gland activation, or even medical procedures like Botox injections that target nerve signals.

Anhidrosis

Conversely, anhidrosis—the inability to sweat normally—poses a serious risk because it prevents the body from cooling itself effectively. People with anhidrosis are more susceptible to heat exhaustion and heatstroke. It can result from nerve damage, skin conditions, or certain genetic disorders.

Maintaining the right balance of sweating is therefore crucial to health and well-being.

The Evolutionary Purpose of Sweating

Humans are one of the few species capable of extensive sweating. This ability gives us a remarkable evolutionary advantage. Unlike most animals that rely on panting or shade-seeking to cool down, humans evolved millions of eccrine glands across their skin. This adaptation allowed early humans to run long distances in hot climates—an ability essential to hunting and survival before the development of tools and agriculture. Sweating thus enabled long endurance activities while preventing heat-related injuries.

Even today, this trait remains one of the reasons humans can adapt to various climates and sustain prolonged physical effort compared to other mammals.

Understanding Body Odor and Hygiene

Sweat itself is usually odorless. The unpleasant smell often associated with sweating arises when bacteria on the skin’s surface break down the components of apocrine sweat. The resulting byproducts—mainly fatty acids and ammonia—cause the distinctive body odor. Good hygiene practices such as regular bathing, antibacterial soaps, antiperspirants, and breathable clothing help control both sweat and odor. Deodorants neutralize odor-causing bacteria, while antiperspirants reduce moisture by temporarily blocking sweat glands.

How to Manage Sweating Naturally

While sweating is natural, there are ways to reduce excessive perspiration and keep it under control:

- Stay hydrated to help the body regulate temperature efficiently.

- Wear lightweight, breathable fabrics, especially cotton or moisture-wicking materials.

- Limit spicy foods, caffeine, and alcohol that can stimulate sweating.

- Maintain a healthy weight to minimize excess body heat.

- Practice relaxation techniques like deep breathing or meditation to manage emotional sweating.

- Use clinical-strength antiperspirants if sweating becomes excessive.

These practical measures support the body’s natural balance without interfering with its crucial cooling functions.

Conclusion

Sweating is far from just an inconvenience—it’s a remarkable biological defense system that keeps our internal environment stable and safe. From regulating temperature to managing emotional responses, sweat plays a vital role in our physical and psychological well-being. Understanding the mechanisms behind it helps us appreciate how the body balances countless factors to protect itself.