Addiction ranks among the most challenging health conditions to address, affecting millions of individuals worldwide and imposing significant social and economic burdens. Despite decades of research and countless treatment programs, the question of “What Causes Addiction, and Why Is It So Hard to Treat?” remains complex, and the struggle to treat it effectively persists. The answer lies not in simple willpower or moral failing, but in a sophisticated interplay of brain chemistry, genetic predisposition, environmental influences, and deeply ingrained neurological changes. Understanding these mechanisms provides insight into both why people develop addictions and why recovery demands such tremendous effort.

The Neurobiology of Addiction: How the Brain Gets Hijacked

At the core of addiction lies a fundamental disruption of the brain’s reward system—a network of neural circuits that has evolved to reinforce behaviors essential for survival, such as eating and reproduction. The primary neurotransmitter involved in this system is dopamine, a chemical messenger that creates feelings of pleasure and motivation. In a healthy brain, natural rewards like food or social interaction trigger a measured release of dopamine, reinforcing these beneficial behaviors.

However, addictive substances and behaviors exploit this system with startling efficiency. Drugs like cocaine, opioids, and methamphetamine cause dopamine to flood the reward pathway at levels ten times higher than natural rewards. This extreme neurochemical surge creates an extraordinarily powerful reinforcement signal that the brain interprets as critically important for survival—despite the substance being actively harmful.

Chronic drug exposure triggers profound molecular changes within the brain. One critical mechanism involves a gene transcription factor called Delta FosB, which accumulates in the nucleus accumbens—a key brain region for reward processing and motivation. The overexpression of Delta FosB is considered the most significant biomolecular mechanism in addiction, necessary and sufficient to produce many of the neural adaptations and behavioral changes observed in addiction. This molecular pathway becomes hyperactive with repeated substance use, intensifying the brain’s compulsive drive to seek and use the substance.

Beyond dopamine, chronic drug exposure causes alterations in gene expression through multiple transcription factors, including cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB). These molecular changes lead to lasting neurological remodeling that essentially rewires the addicted brain, making it fundamentally different from a non-addicted brain at the neurological level.

Recent research has also identified the critical role of neuroinflammation in addiction development. Chronic drug exposure triggers an immune response within the brain driven by support cells called microglia and astrocytes. This neuroinflammatory response, once considered a secondary consequence of addiction, is now understood as a fundamental element in developing and maintaining addictive disorders. The resulting inflammation can lead to widespread neural dysfunction and exacerbate the cycle of drug craving and relapse.

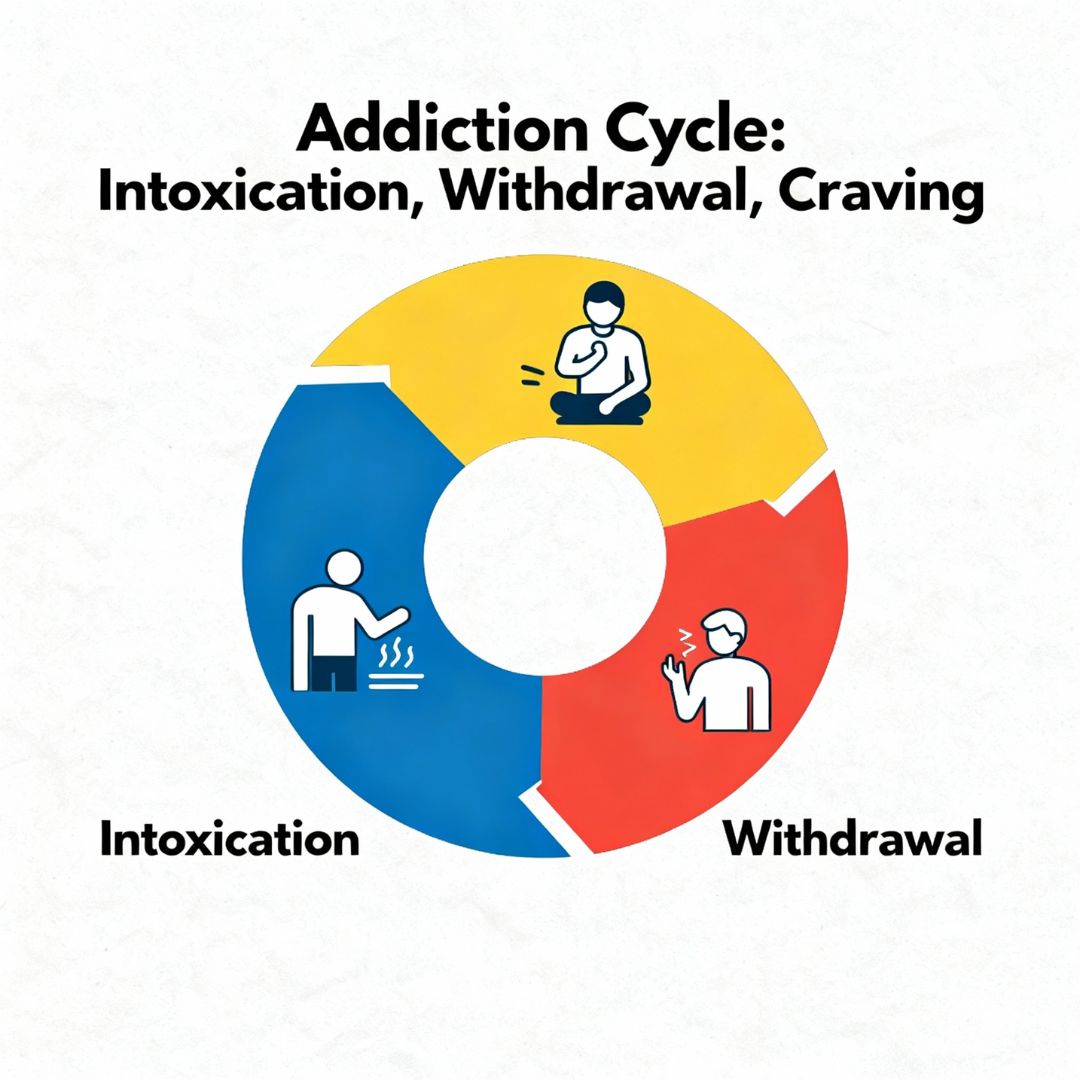

The Three Stages of the Addiction Cycle

Understanding addiction requires recognizing that it operates through distinct neurological stages, each involving specific brain changes:

The Binge/Intoxication Stage occurs when individuals experience the intense pleasurable effects of a substance due to massive dopamine surges in the reward pathway. With repeated exposure, however, the brain adapts through a process called tolerance—requiring higher doses to achieve the same effect. This adaptation marks the beginning of deeper dependency.

The Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage emerges as the brain fundamentally adjusts to chronic substance presence. When the substance is absent, individuals experience withdrawal symptoms including anxiety, depression, irritability, and severe physical discomfort. At this stage, people use substances not for pleasure but to escape these unbearable symptoms, representing a critical transition from voluntary use to compulsive dependence.

The Preoccupation/Anticipation Stage involves intense cravings and compulsive thoughts about substance use. During this phase, the prefrontal cortex—responsible for decision-making and impulse control—shows significantly altered activity. The brain’s ability to evaluate consequences and regulate behavior becomes severely compromised, trapping individuals in a cycle of compulsive use.

Adding complexity to this model is evidence that addicted individuals show blunted dopamine responses to the drug itself, while showing heightened dopamine responses to drug-related cues and craving. This means the brain’s reward system becomes inverted: individuals experience diminished pleasure from the drug but intense craving triggered by environmental reminders, driving continued use in a futile attempt to achieve the expected reward.

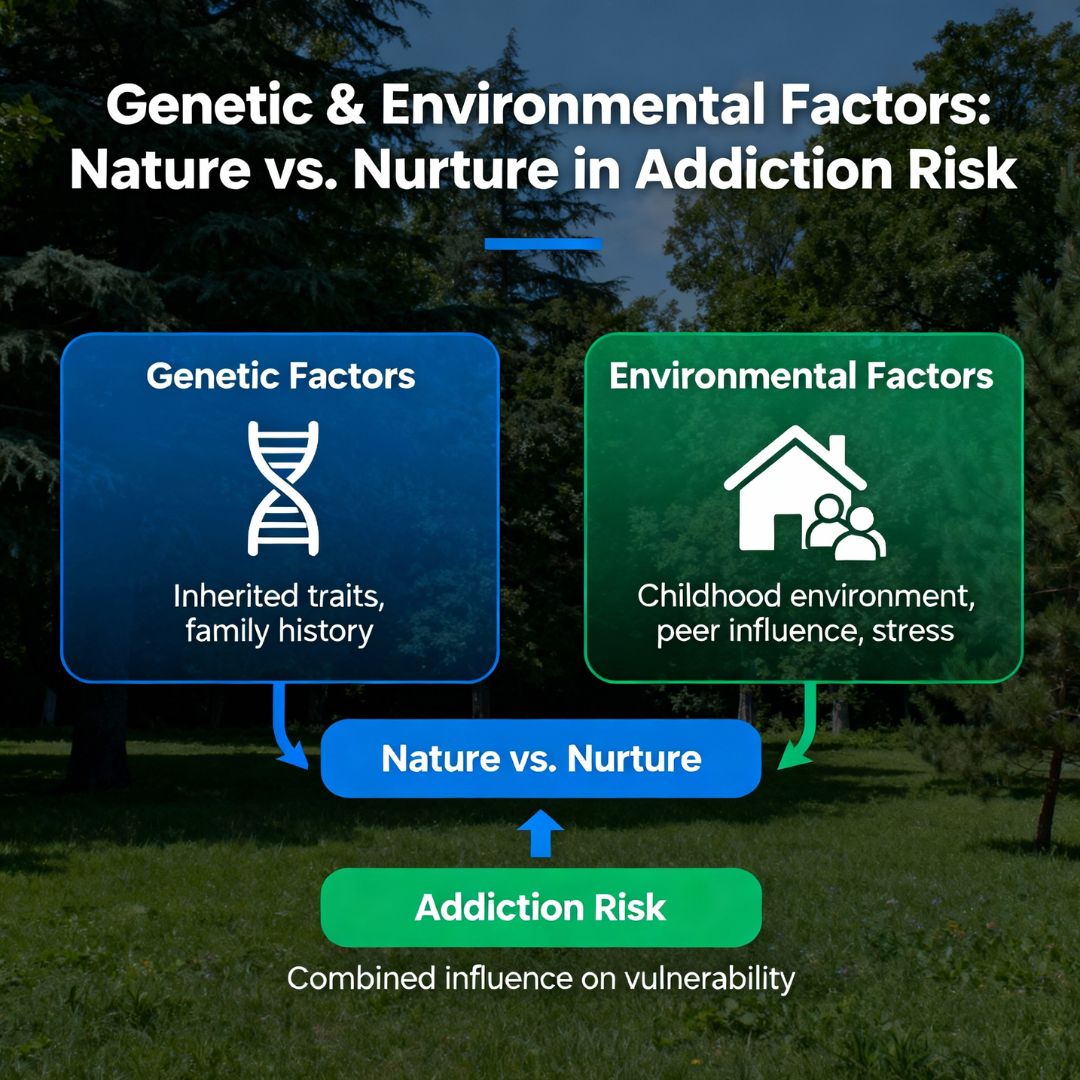

Genetic and Environmental Contributors: Nature and Nurture Combined

The question of whether addiction stems from genetics or environment presents a false dichotomy—it’s decidedly both. Research suggests that genetic factors account for approximately 40-70% of addiction susceptibility, while environmental factors account for the remainder. Importantly, this doesn’t mean addiction is predetermined.

Specific genes influence how the brain processes dopamine and other neurotransmitters. For example, the DRD2 gene affects dopamine processing and has been linked to alcohol addiction, while the SERT gene influences serotonin transport and has connections to drug addiction. However, possessing these genetic risk factors doesn’t guarantee addiction—they simply increase vulnerability.

Environmental factors significantly activate or suppress genetic predispositions. Childhood trauma, chronic stress, exposure to substance use, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), poverty, social isolation, and peer pressure all substantially increase addiction risk, especially for genetically predisposed individuals. A fascinating field called epigenetics reveals how environmental experiences can literally turn genes “on” or “off,” meaning life circumstances can modify which genetic risk factors become active.

Importantly, individuals with no genetic family history of addiction can still develop substance use disorders through environmental exposure and psychological factors, while those with high genetic risk may never develop addiction if protected by supportive environments and positive life experiences.

Why Treatment Is So Difficult: The Multiple Barriers to Recovery

Even understanding addiction’s neurobiology doesn’t fully explain why treatment remains so challenging. The hurdles to successful recovery operate at multiple levels simultaneously.

Physical and Psychological Dependence create formidable obstacles. Physical withdrawal symptoms—tremors, muscle aches, sweating, nausea, and in severe cases, seizures—can be intensely uncomfortable or even life-threatening. Psychological withdrawal involves emotional symptoms like depression, anxiety, anhedonia (inability to feel pleasure), and overwhelming cravings that can persist for extended periods. Unlike physical withdrawal with defined timelines, psychological cravings can endure indefinitely, triggered by people, places, situations, or even sensory cues associated with past substance use.

The Neurobiology of Relapse means that recovery isn’t simply about stopping substance use—it’s about fundamentally rewiring a brain that has been extensively reorganized around addiction. The neural pathways strengthened through chronic drug use remain established even during abstinence, making them vulnerable to reactivation. Studies show relapse rates of approximately 50% within the first 12 weeks after intensive treatment, despite programs costing tens of thousands of dollars and lasting weeks or months.

Structural and Systemic Barriers severely impede access to effective treatment. These include lack of funding and resources, transportation challenges (especially in rural areas), long waiting lists, limited treatment options, financial constraints, and lack of insurance coverage. Additionally, stigma surrounding substance use disorder prevents many from seeking help, while perceived lack of treatment need or low motivation to change reduces treatment engagement.

The Fragmentation of Care represents another critical barrier. Many patients don’t access or remain engaged with treatment after detoxification, partly because addiction services are rarely integrated with medical, psychiatric, and social services. This fragmentation means individuals must navigate multiple separate systems while struggling with active addiction, making adherence to treatment extremely difficult.

Brain Changes in Decision-Making and Executive Function make recovery a neurological challenge beyond willpower. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for impulse control and consequence evaluation, shows decreased activity in addicted individuals. This neural dysfunction means the brain literally struggles with inhibitory control and the ability to learn from adverse consequences.

Current Treatment Approaches and Their Effectiveness

Despite these challenges, evidence-based treatments do work—they simply require comprehensive, sustained approaches.

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) combines FDA-approved medications (methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone) with behavioral therapy. MAT minimizes cravings, blocks some rewarding effects of substances, and decreases continued substance use. Research shows MAT increases patient survival rates, improves treatment retention, and increases employment gains—though it requires ongoing medical management, sometimes indefinitely.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) helps individuals develop coping strategies for cravings, identify triggers, and prevent relapse. Meta-analyses show CBT produces moderate effect sizes compared to minimal treatment, with approximately 42% of CBT patients responding to treatment compared to 19% in control groups. However, CBT’s effectiveness diminishes over longer follow-up periods, suggesting that continued support is essential.

Chronic Disease Management (CDM) approaches treat addiction like diabetes or congestive heart failure—chronic conditions requiring longitudinal care rather than short-term interventions. CDM integrates primary care, specialty addiction services, mental health treatment, and psychosocial support in coordinated, patient-centered approaches. This model shows promise for improving both addiction outcomes and co-occurring medical and psychiatric conditions.

The Bottom Line: Addiction as a Brain Disease Requiring Systemic Solutions

Addiction develops through a complex interaction of genetic vulnerability, environmental circumstances, and profound brain chemistry changes that establish new neural pathways and reward hierarchies. Once established, addiction literally becomes a different disease than the one that started—a chronic brain disorder requiring longitudinal treatment rather than a temporary condition amenable to willpower alone.

Treatment difficulty stems not from ineffective interventions but from the neurological severity of addiction, barriers to accessing treatment, fragmentation of care systems, and the reality that recovery demands sustained effort addressing biological, psychological, and social aspects simultaneously. Understanding addiction through this lens—as a legitimate medical condition rooted in brain pathology—opens pathways toward more compassionate, effective, and comprehensive treatment approaches that recognize both the profound challenge individuals face and the realistic timelines required for meaningful recovery.