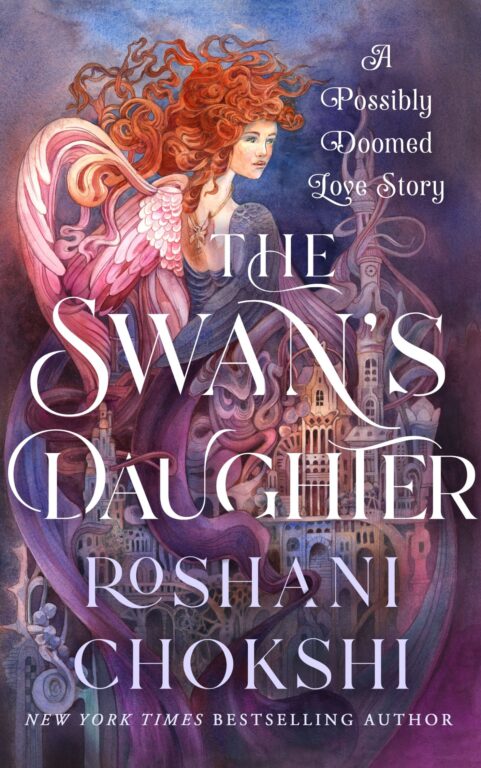

When I picked up The Swan’s Daughter, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. The premise—a cursed prince searching for true love during a deadly bridal tournament—sounded delightfully doomed, but in the best possible way. What I found was something far richer than the typical fairytale retelling that’s become so common lately. This is a book that knows exactly what it’s doing, and it does it with grace, humor, and a surprising amount of heart.

The Setup: A Curse Worth Dying For

Let me start with what drew me in immediately: the curse itself. Prince Arris inherited one of the most ridiculous yet terrifying fates imaginable. Years ago, his father made a poorly worded wish to a sea witch, and now anyone who marries the kingdom’s heir automatically gains the power to rule by literally taking his heart. Previous princes became sentient trees. Their hearts were quite literally harvested.

So when Arris reaches his eighteenth birthday, his parents do what any logical royal family would do—they announce a tournament. If Arris must marry a potential murderer, they reason, at least he’ll have options and can try to find true love in the process. The hope is that genuine love might break the curse. It’s darkly amusing, and it immediately sets up the central tension of the book without feeling contrived.

Then there’s Demelza. She’s the seventh daughter of a veritas swan and an evil, immortal sorcerer—a combination that makes her simultaneously powerful and unwanted. Her song compels anyone who hears it to tell the absolute truth. Unlike her siblings, who possess wings and beautiful voices suited to their father’s sinister plans of conquest, Demelza was born flightless and with a voice that sounds, by her own admission, absolutely terrible. She’s spent her life feeling utterly useless, watching her sisters get recruited for their father’s schemes while she’s left behind.

When she encounters Arris, they strike a deal: he offers her sanctuary in the castle, and she uses her truth-singing to help him identify which of his potential brides actually care for him versus those hunting his heart for power. It’s a partnership that becomes so much more.

The Characters: Quirky, Flawed, Devastatingly Real

What impressed me most about Chokshi’s characterization is her refusal to make either protagonist conventionally heroic. Arris is openly eccentric—he goes barefoot constantly, has intense sensory fixations, and genuinely tries to find something redeeming in everyone, even people actively plotting to murder him. His sister Yvelle, a snarky necromancer royal, calls him out for this at one point: “This is part of the reason why women keep trying to kill you, Brother.” It’s hilarious, but it also reveals the book’s gift for balancing darkness with genuine humor.

Demelza, meanwhile, is dealing with something more insidious: the internalized belief that she’s fundamentally broken. She’s never been taught to dream or imagine a future for herself. Her character arc isn’t about gaining magical powers or suddenly becoming conventionally beautiful—it’s about learning that she deserves to exist for her own sake, not just to be useful to others. And the way Chokshi handles this journey feels earned, never preachy.

The relationship between Demelza and Arris develops in a way that surprised me. These are two people who recognize something dangerous in each other’s capacity to love. For Demelza, loving feels like losing control and surrendering her hard-won independence. For Arris, who falls a bit too easily for everyone, true love with Demelza requires actual vulnerability and honesty in a way his previous infatuations never did. When they finally understand what they feel, it hits differently than typical YA romance because we’ve earned the emotional weight of that recognition.

The supporting cast deserves mention too. Arris’s mother, Queen Yzara, is a powerful woman who genuinely loves her son while sending him toward his probable death—there’s genuine complexity there, not just a one-dimensional villain or saint. Demelza’s mother, Araminta, is similarly nuanced: fiercely protective in ways Demelza misinterprets as indifference. The competing brides aren’t just obstacles; they’re strange, magical, fascinating people with their own logic and motivations.

The Worldbuilding: Magic as Beauty, Not Just Plot Device

Here’s where The Swan’s Daughter truly shines. The Isle of Malys feels alive in a way that most fantasy worlds don’t. Magic isn’t deployed here as a problem-solving tool or a way to punch the plot forward—it’s woven into the fabric of how this world simply is.

The environments feel deliberately impossible in the best fairytale tradition. There are ozorald caves hosting glittering balls, daydream trees in menageries, pearl crocodiles, glass boats, and buildings that respond to the needs of their inhabitants like devoted servants who’ve watched their charges grow from childhood. Argento, the sentient grandfather apple tree who prefers grumpy wisdom, is simultaneously funny and genuinely touching.

What I appreciated is that Chokshi doesn’t make the fantasy elements feel random or cluttered. Each magical detail serves the atmosphere and the book’s themes about transformation, beauty, and acceptance. A curse isn’t simply evil—it’s a twisted thing with layers of consequence that depends entirely on how characters interpret and respond to it. Even necromancers aren’t presented as inherently evil; they’re just… quirky magical practitioners going about their business.

The book also contains a refreshing lack of spectacular magical battles. In a genre increasingly dominated by action sequences, The Swan’s Daughter trusts that character relationships, emotional stakes, and the whimsy of a fairytale atmosphere are enough to carry the narrative. And frankly, it’s right.

The Prose: Lyrical Without Being Purple

Chokshi’s writing here is genuinely lovely. She has a gift for sensory detail that brings moments alive—the smell of earth and fallen plums, the texture of leaves underfoot, the taste of apples that change flavor with each season. The prose style is sometimes distant and formal in a way that echoes classic fairytale narration, which initially creates a slight barrier between reader and character, but it actually strengthens the book’s atmosphere.

The dialogue balances whimsy with genuine character voice. There’s real humor here—not forced comedic relief, but the natural comedy that emerges when eccentric people interact. A conversation between Arris and Yvelle about his tendency to appreciate (or romanticize) everyone trying to murder him is both funny and revealing.

What Didn’t Quite Land

I do want to note that the romantic progression, particularly on Arris’s end, can feel a bit rushed. Arris has a history of falling quickly for people, and while the book acknowledges this flaw, it doesn’t always feel like the romantic stakes between him and Demelza develop with the tension you might expect. The book knows this is a theme—loving someone despite uncertainty—but the execution of their crucial romantic moments could have carried more weight. This isn’t a dealbreaker, but it’s the one place where the emotional intensity dips below what the stakes suggest.

Additionally, some readers might find the distant, fairytale-like narration takes a bit longer to warm to than more intimate third-person prose. If you prefer being deep inside characters’ heads, the narrative perspective here might feel slightly remote. That said, I found it created the perfect tonal match for the story Chokshi wanted to tell.

Final Thoughts: Why This Book Matters

The Swan’s Daughter arrives at a moment when YA fantasy often tries too hard to be “dark” or “gritty” by subverting fairytale expectations entirely. What’s refreshing here is that Chokshi subverts fairytale tropes while maintaining genuine respect for them. This book doesn’t mock the genre it inhabits—it inhabits it fully and then adds layers of emotional complexity underneath.

The central question the book grapples with—what it means to love when love itself is dangerous, when tomorrow isn’t guaranteed, when being loved could literally kill you—feels resonant in ways both fairytale and contemporary. Both Arris and Demelza are searching for confirmation that they’re worthy of love, and that search, more than any magical element, is what drives the narrative forward.

At its heart, The Swan’s Daughter argues that the bravest thing you can do isn’t survive—it’s find the courage to actually live, to choose connection despite the risk, to transform on your own terms rather than for others’ expectations. In a fairytale universe filled with magic and whimsy, that’s somehow the most magical element of all.

If you love lush, character-driven fantasy with genuine wit and heart, if you’re looking for a fairytale that trusts its readers enough not to explain every metaphor, and if you want a romance that earns its emotional beats through genuine understanding between characters—The Swan’s Daughter is absolutely worth your time. It’s the kind of book that makes you want to reread passages just to savor the language, and that sticks with you long after you’ve finished.author/show/13695109.Roshani_Chokshi”>