In the late 1600s, Isaac Newton wasn’t only the man behind the discovery of gravity—he was also willing to put his own eyesight in danger to unravel how vision works. In a set of daring (and undeniably unsafe) experiments, Newton violated the two biggest rules of eye safety: he stared straight at the sun and even slid a needle beneath his eyeball. His mission was to understand the mysterious lights and colors that appear when our eyes are closed. If you’ve ever gazed into a campfire or caught an accidental glimpse of the sun, you may have seen shimmering patterns dance across your vision. These fleeting illusions fall under the strange science of afterimages, a phenomenon that continues to puzzle researchers even today.

How the Eye Turns Light into Vision

The story begins inside the retina—the light-sensitive layer at the back of the eye. Here, millions of specialized cells known as photoreceptors absorb incoming light and convert it into electrical signals that the brain can interpret.

Each photoreceptor contains thousands of tiny molecules called photopigments, which are tuned to specific colors. When light particles, or photons, strike these pigments, they trigger a change in the molecule’s structure. This process, known as bleaching, temporarily alters the photopigment and sets off a chain of chemical reactions. The result is an electrical impulse that travels to the brain.

By combining the signals from roughly 200 million photoreceptors, the brain forms the images we see every moment. But sometimes, those signals linger even after the light source disappears. That’s when afterimages occur.

Positive Afterimages: When Light Refuses to Fade

One explanation for afterimages is that they originate in the photoreceptors themselves. Staring at something bright, like a campfire, overwhelms the photopigments and leaves many of them in a bleached state. While they regenerate, they can’t absorb light as efficiently.

Yet, for a short time, the photoreceptors continue sending signals to the brain as if the light were still there. This produces a glowing illusion called a positive afterimage—the same bright shapes and patterns you notice when you close your eyes after staring at the sun or a flame.

Positive afterimages fade within seconds, but sometimes they transform into something more curious: a negative afterimage.

Negative Afterimages: Colors That Flip

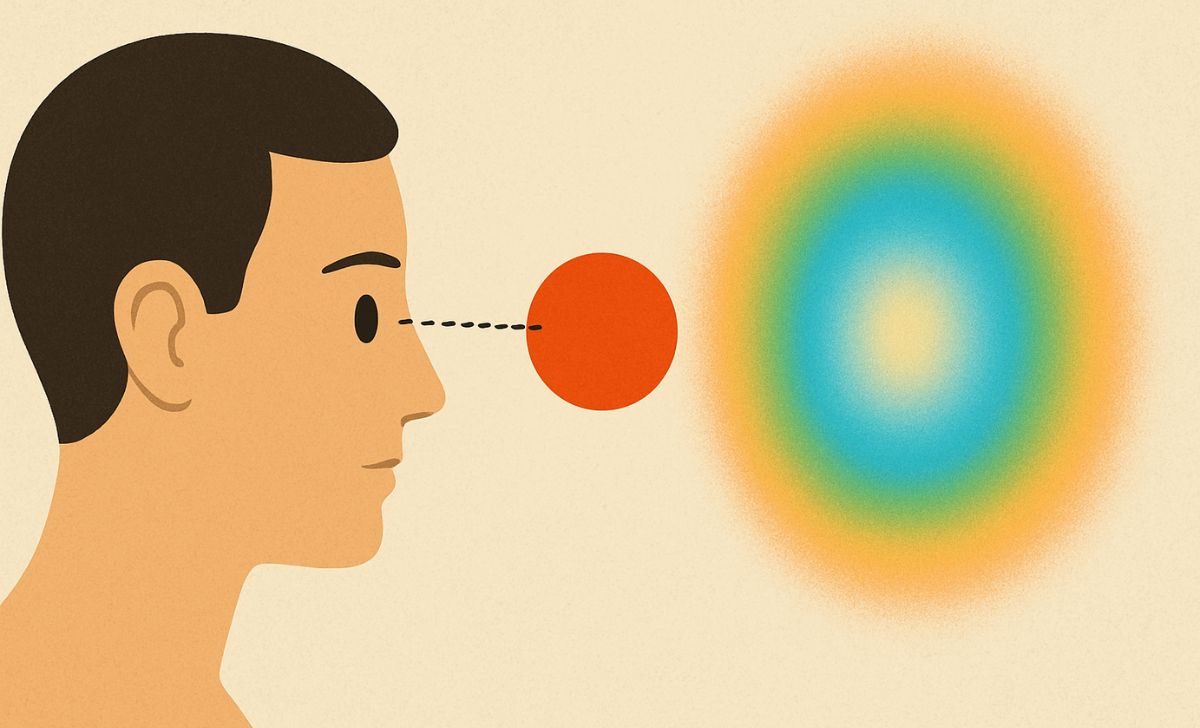

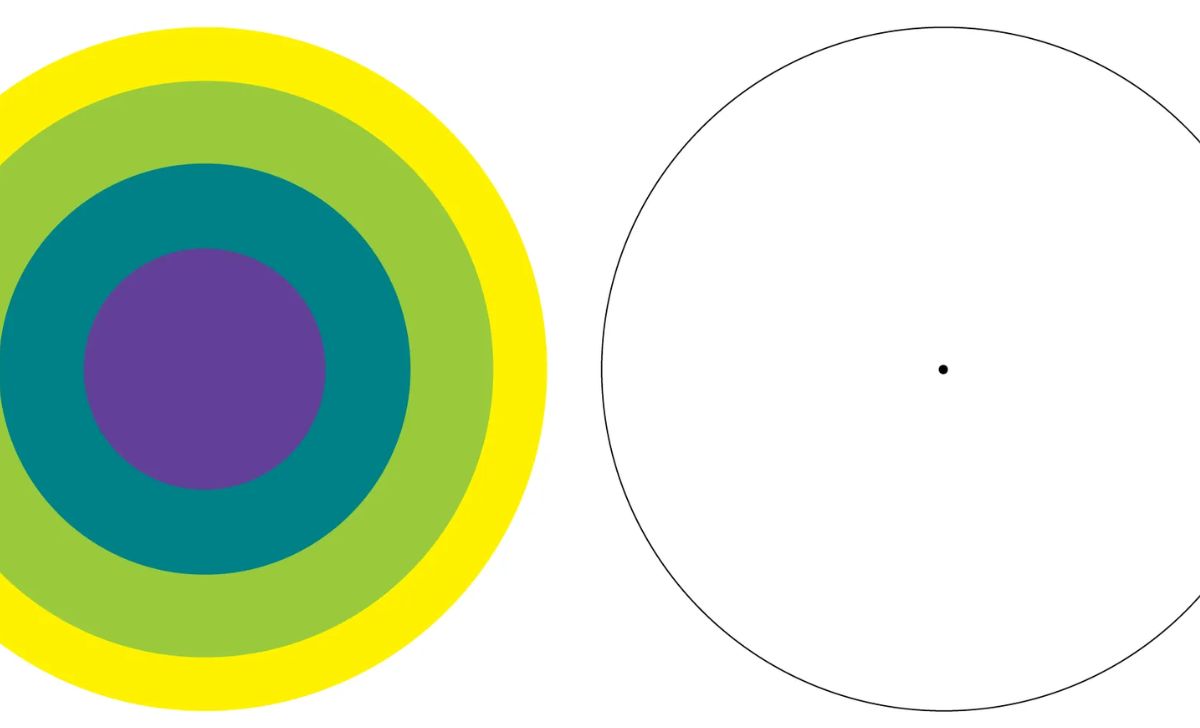

A negative afterimage occurs when the colors of the original image seem to invert into their opposites. For example, stare at a bright green flower on a yellow background. If you then close your eyes or look at a white surface, you’ll see a magenta flower on a blue background.

Why does this happen? Scientists aren’t entirely certain, but several theories exist.

- Photoreceptor fatigue theory: Cells sensitive to one color, such as green, become exhausted after prolonged exposure. Their counterparts—red-sensitive cells, which are normally balanced against green—remain fresh. When you shift your gaze, the red cells dominate, creating the illusion of complementary colors.

- Ganglion cell theory: Some researchers believe the effect originates deeper in the retina, in a layer of neurons called ganglion cells, which process color signals before passing them to the brain.

- Brain processing theory: Others argue the phenomenon results from higher-level processing in the brain itself, rather than just the retina.

Whatever the source, the result is a striking reminder that our visual system doesn’t simply record reality—it interprets it, sometimes in surprising ways.

Pressure Phosphenes: Seeing Without Light

Newton’s experiments went even further when he pressed and prodded his own eye with a needle. Disturbing as it sounds, this created vivid circles of light and color—what we now call pressure phosphenes.

Newton believed these luminous shapes appeared because he was physically bending his retina. Modern scientists partly agree: rubbing or pressing on the eye can stretch the delicate neurons, causing photoreceptors to misfire and send false signals to the brain.

But pressure isn’t the only way to create phosphenes.

- Magnetic stimulation: In certain medical procedures, doctors use magnetic pulses on the brain. Patients sometimes report seeing flashes of light, even if they are blind in the eyes themselves.

- Cosmic radiation: Astronauts traveling through space often describe seeing mysterious bursts of light when cosmic rays from the Sun or distant stars pass through their bodies. In the weightlessness of space, even the absence of air and atmosphere can’t shield the human eye from these strange visual fireworks.

Newton’s Curiosity and the Mysteries That Remain

Isaac Newton may have taken extreme risks to unlock the mysteries of vision, but his curiosity opened doors to discoveries that continue to intrigue scientists today. Afterimages, whether positive or negative, reveal the complex interplay between light, photoreceptors, and the brain. Pressure phosphenes, meanwhile, show that vision doesn’t always require light at all—sometimes the brain itself creates it.

Yet, for all we know, much remains unanswered. Why exactly do negative afterimages occur? How do phosphenes form in complete darkness? Even today, centuries after Newton risked his sight, these questions remain at the edge of science.