Deep within the ancient Palace of Knossos on the island of Crete, according to Greek mythology, lay one of the most elaborate and terrifying structures ever conceived: the Labyrinth. And dwelling at its heart was a creature of unimaginable horror—the Minotaur, a monstrous being with the body of a man and the head of a bull. This myth, which has captivated audiences for over three millennia, is far more than a simple tale of a hero slaying a beast. It is a rich narrative woven with themes of revenge, divine punishment, sacrifice, and the triumph of courage over seemingly insurmountable odds. The story of the Minotaur and the Labyrinth represents a crucial moment in Greek mythology where heroism, cleverness, and love converge to break the chains of a cruel tribute and forever change the course of history.

The Birth of a Monster: Divine Revenge and Unnatural Union

The origins of the Minotaur are rooted in hubris, divine retribution, and an act of divine desperation that sets the stage for centuries of suffering. The tale begins not with the monster itself, but with King Minos of Crete and his relationship with the god Poseidon. Minos had prayed to Poseidon to send him a magnificent white bull from the sea, promising to sacrifice the animal to honor the god. Poseidon, god of the sea and earthquakes, answered this prayer and sent a snow-white bull of extraordinary beauty—the Cretan Bull—from the depths of the ocean.

However, King Minos, enchanted by the animal’s magnificence, made a fateful decision: he refused to sacrifice the bull as promised. Instead, he kept the magnificent creature for his own herd and sacrificed an inferior animal in its place. This act of betrayal and disrespect toward the gods would exact a terrible price, not only for Minos but for his entire kingdom and the innocent people of Athens.

Poseidon, outraged by Minos’s treachery, devised a punishment of extraordinary cruelty. With the assistance of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, Poseidon cursed Queen Pasiphae, the wife of King Minos, with an unnatural and obsessive lust for the very bull that her husband had refused to sacrifice. Pasiphae, who was herself of divine descent as the daughter of the sun god Helios and sister to the enchantress Circe, found herself consumed by a desire that was both impossible and humiliating to fulfill.

Desperate and consumed by this curse, Pasiphae turned to Daedalus, the legendary inventor and architect who had come to Crete to escape banishment from Athens after murdering his nephew. Daedalus, one of the greatest craftsmen of the ancient world, devised an ingenious solution to this impossible predicament: he constructed a hollow wooden cow covered with realistic cow hide, so authentic that it fooled the Cretan Bull. Within this wooden construct, Pasiphae hid herself, allowing the bull to mate with her. The result was a pregnancy that would give birth to one of mythology’s most terrifying creatures.

Pasiphae gave birth to a half-human, half-bull child—a creature with the body of a man and the head and tail of a bull. The infant was initially named Asterion (or Asterius), after the sacred king of Crete, but history would know him by another name: the Minotaur, literally meaning “the bull of Minos.” According to the ancient accounts, this creature fed exclusively on human flesh, making it a monster unlike any other in the mythological world.

The Labyrinth: A Prison of Genius Design

With the creature born and the kingdom now burdened with a shameful secret, King Minos faced an unprecedented crisis. He could not simply execute the monster—it was his wife’s offspring, after all—yet he could not allow it to roam free. The solution came from the mind of the same architect who had enabled its birth: Daedalus.

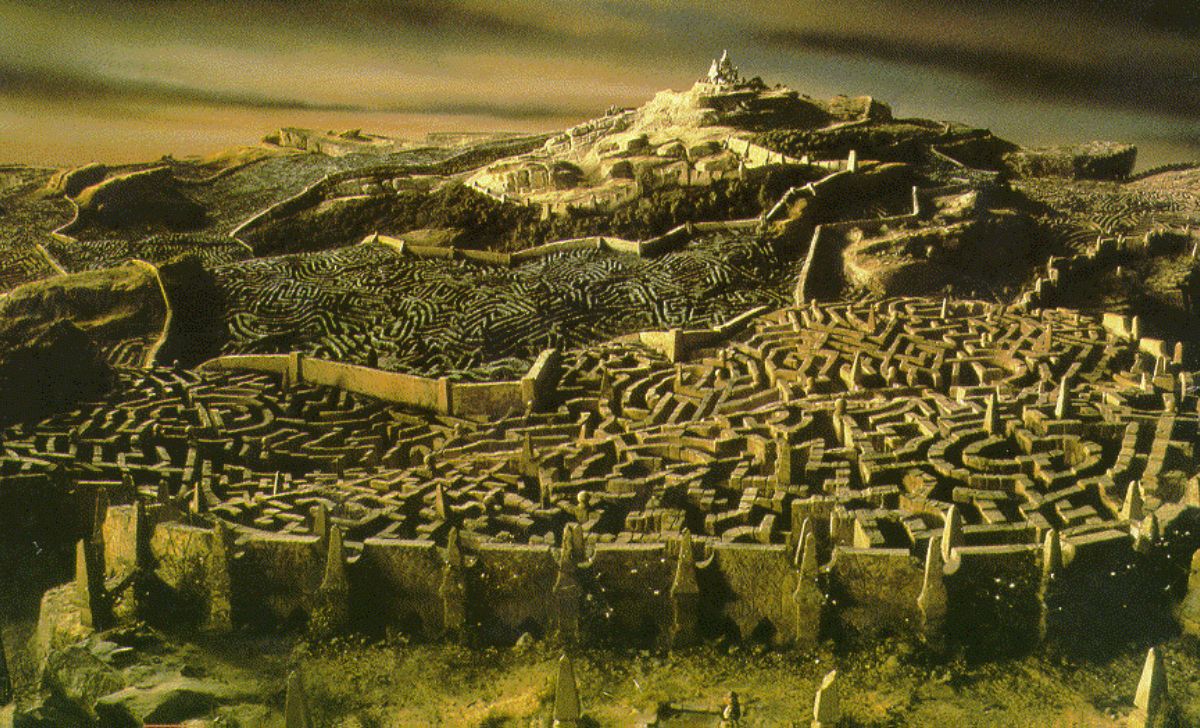

Minos commanded Daedalus to design a structure so complex and confusing that no one who entered it could possibly escape—a building that would serve as both prison and execution chamber. Daedalus rose to the challenge and created the Labyrinth, an elaborate maze-like construction that was, according to later classical sources, so cunningly designed that even Daedalus himself could barely escape it after construction. The Labyrinth’s winding passages, dead ends, and disorienting corridors made it virtually impossible for anyone to navigate. The structure likely drew inspiration from the Palace of Knossos itself, which featured an actual complex layout with twisting hallways and multiple chambers, and some archaeologists believe the myth may have been inspired by this real architectural marvel.

At the very center of this inescapable maze, the Minotaur was imprisoned, fed and hidden away from view. The creature’s existence became Crete’s darkest secret—a shameful reminder of both divine punishment and the consequences of defying the gods.

The Cruel Tribute: Athens in Bondage

The Minotaur’s imprisonment might have remained an isolated horror had it not been for another tragedy that would connect the fates of Athens and Crete. Minos had a son named Androgeos, a young man of exceptional talent who competed in athletic games across the Mediterranean. When Androgeos journeyed to Athens to participate in the Panathenaic Games, the annual competition held to honor the goddess Athena, he achieved victories that earned the jealousy of the Athenians. In a fit of envy, the Athenians killed Androgeos, an act that would incur the wrath of King Minos.

Minos declared war on Athens, and with the assistance of Zeus himself, the Cretan king defeated the Athenian forces. Rather than destroy the city entirely, Minos imposed a devastating tribute: every nine years (or according to some accounts, every year), Athens was compelled to send fourteen of its most noble young citizens—seven youths and seven maidens—to Crete to be sacrificed to the Minotaur. These innocent tributes would be sent to their deaths, thrown into the Labyrinth to be hunted and consumed by the monster. The tribute represented not merely a political punishment, but a systematic decimation of Athens’s best and brightest, a constant reminder of Cretan dominance and Athenian humiliation.

This cruel practice continued for generations, and each nine-year cycle brought fresh grief to Athens. The city mourned its lost children while feeling powerless to resist the might of King Minos. The tribute became more than a political obligation—it was a symbol of Athens’s subjugation and a wound that never healed.

The Hero’s Arrival: Theseus Volunteers

Into this dark era stepped a young man whose courage would change everything: Theseus, the son of King Aegeus of Athens. Theseus is often regarded as the founding hero of Athens, and when the third time for sacrifice arrived, he made a decision that would define his legacy. Rather than wait to be chosen among the tributes, Theseus volunteered to go to Crete himself, determined to slay the Minotaur and end the brutal practice that had tormented his city for so long.

Theseus’s motivation was not merely personal glory, though such aspirations certainly motivated many Greek heroes. According to ancient sources, Theseus believed that any ruler who would allow his city to continue paying such a terrible tribute had no right to rule at all. He could not, in good conscience, see his fellow citizens sent to their deaths. Before departing for Crete, Theseus made a solemn promise to his father, King Aegeus. If he succeeded in slaying the Minotaur and returned home safely, he would replace the black sails of the ship carrying the tributes with white sails as a signal of his victory. If he perished, the black sails would remain, signifying his failure and death.

Ariadne’s Love: The Thread of Hope

Upon arrival in Crete, Theseus was brought into the presence of King Minos and his family. It was there that fate intervened in an unexpected way: Ariadne, the beautiful daughter of King Minos and Queen Pasiphae, fell deeply in love with the heroic Athenian prince. As Ariadne observed Theseus, she recognized not merely a handsome visitor, but a doomed young man who had little chance of survival in the Labyrinth, even if he managed to slay the Minotaur. She understood what King Minos seemed confident about: that even a victorious hero would be hopelessly lost in Daedalus’s impossible maze.

Moved by compassion and love, Ariadne resolved to help Theseus. She approached Daedalus, the maze’s architect, and begged him to reveal the secret of the Labyrinth. Whether moved by sympathy for Theseus, nostalgia for his native Athens, or simply recognizing that the cycle of tribute should end, Daedalus eventually shared his knowledge with the princess.

On the night before Theseus was to enter the Labyrinth, Ariadne gave him two crucial items. The first was a sword, which Theseus had managed to smuggle through his tunic despite being stripped of weapons upon arrival in Crete. The second, and far more important, was a ball of thread—often referred to as “Ariadne’s thread” or the “clew.” Ariadne instructed Theseus to tie one end of the thread to the entrance of the Labyrinth as he began his journey inward, then unroll it as he navigated deeper into the maze. By following the thread back, Theseus would be able to retrace his steps and escape, regardless of how complex and confusing the Labyrinth’s passages might be. In exchange for her help, Theseus promised to marry Ariadne and take her away from Crete.

The Confrontation: Slaying the Monster

With thread in hand and sword concealed, Theseus entered the Labyrinth. Carefully unwinding the thread as he advanced, he navigated through winding passages and dead ends, following the instructions that Daedalus had given Ariadne: go forward, always go down, but never turn left or right. Hours passed as Theseus descended deeper into the maze, guided only by the thread and the knowledge that somewhere in this impossible structure awaited the Minotaur.

Different accounts describe the confrontation in various ways. Some versions suggest that Theseus found the Minotaur sleeping, while others describe an immediate and fierce battle. In one particularly vivid account, Theseus discovered a dead-end passage with a hidden turning—exactly the kind of dead end shown on the map that Daedalus had shared. Theseus hid around this final corner and called out to the Minotaur. The enraged beast, hearing the call, charged down the passage with such fury and momentum that it could not slow itself before the hidden turn and crashed headlong into the wall, stunning itself. While the creature was dazed, Theseus struck decisively.

The actual means of the Minotaur’s death varies depending on the source. Some accounts describe Theseus using the sword that Ariadne provided, striking the beast in the throat. Others speak of him strangling the creature with his bare hands or bludgeoning it with a club. Regardless of the specific method, all accounts agree that Theseus, through strength, courage, and cunning, ultimately prevailed over the monster. The beast that had claimed countless victims over the years fell to the Athenian hero, and with it fell an entire system of tribute and suffering.

The Escape and Tragic Consequences

With the Minotaur slain, the real challenge began: escaping the Labyrinth. But Theseus was prepared. He gathered the thread, following it back through the maze’s confusing passages until he emerged at the entrance where Ariadne anxiously awaited him. He also freed the other thirteen Athenian tributes who had been imprisoned, leading them toward escape.

Theseus, Ariadne, and the freed tributes quickly fled to their ship and set sail for Athens. However, their journey home was not to be straightforward. On the island of Naxos, either due to circumstance or deliberate choice, Theseus abandoned Ariadne as she slept on the beach, leaving her alone and vulnerable. Some accounts suggest this betrayal was divine punishment; others indicate that Theseus simply abandoned his promise of marriage. Ariadne’s despair and heartbreak seemed absolute—until the god Dionysus discovered her on the island, fell in love with her, and took her as his divine bride, becoming the only Greek god to remain faithful to his wife.

As Theseus’s ship sailed toward Athens, triumph gave way to tragedy. In the excitement and chaos of escape and celebration, Theseus forgot the crucial promise he had made to his father before departing for Crete: to change the black sails to white upon his successful return. As the ship approached the harbor at Athens, it still flew the black sails of death and mourning.

King Aegeus, who had been watching from Cape Sounion, the highest cliff overlooking the sea, saw the black-sailed ship approaching. Believing his beloved son had perished and that the Minotaur had claimed another victim, Aegeus was overwhelmed with grief. In his despair, he threw himself from the cliff into the sea below, drowning in the waters that would henceforth bear his name: the Aegean Sea. Thus, while Theseus’s heroic act freed Athens from its cruel tribute, it inadvertently cost his father his life—a tragic price for victory.