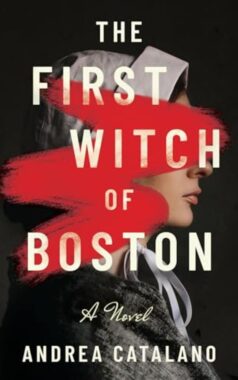

The First Witch of Boston opens like a hand being laid on history—firm, patient, and intent on revealing the small cruelties and larger systems that crushed one woman’s life. In The First Witch of Boston, Andrea Catalano takes the fragmentary records of seventeenth-century New England and builds a novel that is at once intimate and public: intimate in the way it lives inside the accused woman’s thoughts and daily routines, and public in the way it demonstrates how gossip, law, and gender combined to produce a conviction. This review looks at how Catalano shapes those pieces into a story, where it succeeds, and where the novel’s choices might divide readers.

Setting and historical research

Catalano’s Boston is tactile and exact. The book is set in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1640s, and the minutiae of domestic life—hearth routines, herbal remedies, cramped courtrooms—are written with the confidence of careful research. Readers who enjoy historically grounded fiction will appreciate that the novel does not simply borrow period color; it uses archival details (diary excerpts, court testimony echoes) to animate scenes of accusation and examination. Multiple reviewers and early readers have called out the author’s research as a major strength, noting that the legal and social procedures around witchcraft trials are rendered with disturbing specificity.

Plot overview (contains plot information)

Thomas and Margaret Jones arrive from England seeking a fresh start in Boston. Margaret, a healer by trade and temperament, tends to neighbors, uses knowledge of herbs, and speaks with a candor that unsettles a highly stratified Puritan community. As tensions rise—born of scarcity, jealousy, and superstition—rumors about Margaret harden into accusations. The core of the plot follows the slow escalation from suspicion to formal charges: humiliating examinations, the ways “evidence” is manufactured, and the social pressures that push witnesses and jurors toward conviction. Alongside the courtroom drama the book threads quieter scenes—relationships within the town, the pregnancy that heightens stakes for Margaret and Thomas, and the private moments that humanize a woman otherwise reduced to a label by her accusers. The narrative arc culminates in trial and its aftermath, but Catalano devotes just as much energy to the social environment that made the trial possible.

Characters and performances

Margaret is the novel’s beating heart: stubborn, skilled, and deeply human. Catalano resists turning her into an abstract martyr; instead she is flawed, often blunt, sometimes tender. Thomas serves as a counterpoint—more cautious, painfully aware of social boundaries, and torn between protection and survival. Secondary characters—religious leaders, neighbors, and those who both enable and resist the accusations—are sketched with enough complexity to avoid caricature. Several reviewers have praised this balance, noting that Catalano’s portrayal of community dynamics is what elevates the book beyond a simple courtroom drama. The audiobook reception has been more mixed: listeners admired the storytelling but some found elements of the narration (notably emotional peaks) uneven.

Themes and tone

At its center the novel interrogates power—who holds it, how it is exercised, and how communities weaponize belief. Gender and knowledge are persistent motifs: women whose skills threaten normative roles risk being read as dangerous. Catalano explores how fear and economics often sit underneath accusations presented as piety. The tone is mournful without being sentimental; there’s anger in the prose but it’s directed at systems rather than at isolated villains. Multiple reviewers have pointed out that the book’s moral clarity—solid and necessary—never becomes didactic, allowing readers to feel the gulf between private truth and public condemnation.

Pacing, structure, and prose

Catalano favors a measured pace. The novel lingers on domestic scenes and social interactions, which pays off when the cumulative pressure of rumor and ritual finally snaps into overt action. Readers who prefer propulsive plots might find sections slow, but those same readers will likely acknowledge that the slower pace produces a richer payoff: the trial’s horror lands because the book has made us care about what’s at stake. The prose is plain but evocative—sufficiently modern to be readable, yet attentive to period rhythms. Some critics noted occasional melodramatic moments; others saw those moments as faithful to the intensity of panic in small communities. On balance, early reaction has praised Catalano’s voice as both accessible and literate.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths: emotional clarity, strong world-building, and a willingness to linger on ordinary life so the injustice feels personal. Catalano’s handling of legal detail is another highlight—the mechanics of accusation and evidence are painful to read because they feel plausible and historically grounded. Limitations: the book’s commitment to a focused moral argument sometimes flattens minor characters who might have benefited from deeper interiority; pacing will not suit readers who prefer a faster, plot-driven historical thriller. A few reader reports also point to scenes that could feel repetitive in tone, which may blunt momentum for some.

Who should read this book

If you enjoy historically anchored fiction that examines social injustice—think readers of Ariel Lawhon or Chris Bohjalian—this will resonate. It’s a good match for book clubs because the moral and historical questions catalyze discussion: How does a community justify cruelty? What role do gender and expertise play in social exclusion? Listeners of audiobooks should read a sample first to check narration style. Casual readers seeking a breezy read might find this weightier than expected.

Final thoughts

The First Witch of Boston is a compassionate, rigorously researched novel that turns a courtroom record into a living person. Catalano succeeds at making history feel immediate—less a distant artifact and more a mirror that reflects persistent patterns of fear, power, and scapegoating. It’s the kind of book that lingers, not because of theatrical set pieces, but because it shows how everyday acts—talk over a fence, an ill-timed remark, a medical cure—can be reshaped into a social death sentence when institutions want an example. For readers who value character-driven historical fiction with moral clarity, this is a rewarding and necessary read.