What makes a book a book? Is it simply any object that stores ideas, or is it the smell of pages, the heft in your hands, and the way a cover promises an inside world? Those questions pull us both backward and forward at once. To answer them, we have to trace the evolution of the book—how its parts—pages, type, ink, and binding—slowly stitched together into the cultural object we still call a “book,” and then ask whether that identity survives when the pages vanish into glass and light.

The codex: when pages learned to be together

Long before hardbacks and Kindles, people used scrolls, papyrus rolls, and the occasional carved tablet to carry words. The codex — a stack of separate pages bound along one edge — flipped that idea on its head. Suddenly readers could flip directly to a passage instead of unrolling meters of text. That practical advantage quietly reshaped how people read and how authors organized material. The codex’s format made reference, index, and narrative structure easier to manage, and it set the stage for what most of us still picture when we hear the word “book.”

Gutenberg — not the first inventor, but the spark that changed everything

Moveable type existed in various forms outside Europe before the 15th century, but Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press rearranged power. By mechanizing the process of reproducing text, printing moved the gatekeepers of knowledge away from monasteries and courts and into shopfronts and marketplaces. Suddenly copies could multiply quickly and cheaply; print shops spread across cities; pamphlets, maps, and broadsheets carried news, argument, and art into a much wider public. The printing revolution didn’t invent books from thin air — it amplified demand for them, standardized production, and made texts an ordinary part of civic life.

Paper, ink, and type: the quiet technologies that made reading possible

A book’s skeleton is deceptively simple: a writing surface, marks that form language, and something to hold them together. Paper, as a practical, cheap writing surface, came out of East Asia long before it dominated Europe; earlier still was papyrus in Egypt. In Europe, durable parchments and wooden sheets held texts until paper’s cost-effectiveness won out for mass printing.

Ink changed too. Early inks that worked for handwriting didn’t cling well to metal type, so printers adopted oil-based mixtures — soot or pigment mixed with oils and resins — that scored well against the pressures of a press. Type itself began as handcrafted, reversed letters cast on little metal blocks; before industrial standardization, fonts varied almost as much as handwriting. The first waves of Roman typefaces — the ancestors of things like Times New Roman — arose from craftsmen who reduced letterforms to repeatable molds. Type wasn’t just utility: it shaped tone. A font’s weight and spacing influence how a text feels to a reader, much like an accent colors a spoken sentence.

Covers, spines, and design — form catches function

Early books were pragmatic: covers of wood or pasted sheets of paper protected pages. Later, millboard and rope-fiber boards offered cheaper and more consistent options for binding. What became the modern cover moved from protection into persuasion — cover art turned into a marketing tool, a first impression that promised genre and mood. Spines developed their own history too. Flat spines made books lie comfortably on a table for reading; rounding a spine solved durability issues but introduced new mechanical problems, like a book wanting to close on itself. Bookbinders learned to balance flexibility, longevity, and ease of handling — choices that still separate a pocket paperback from a library folio.

The sensory book: weight, smell, and ritual

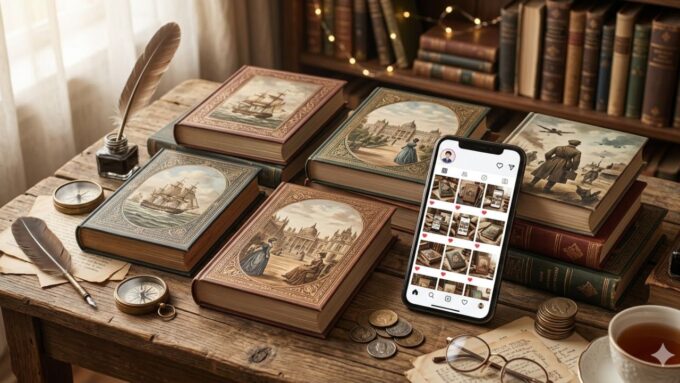

People don’t just read with their eyes. The experience of a physical book involves sound, touch, and scent. The rustle of a page, the give of a softcover, the faint, dusty perfume of aging paper — these are cues that prime memory and attention. For many readers, those cues create a ritual around reading: choosing where to sit, how to carry a book, the small pleasures of bookmarking and dog-earing. Those acts add layers to a text’s meaning in ways that go beyond pure words.

Pixel books and e-ink: the book transformed, not erased

When screens and e-ink arrived, they didn’t so much kill books as shift their affordances. E-readers tuck libraries into a pocket, and digital distribution removes many of the physical barriers Gutenberg’s presses once imposed. Formats like EPUB and PDF carry the same words but allow features that print never could: adjustable font sizes, search, hyperlinks, and near-instant global delivery. Audiobooks add another dimension: voice, cadence, and performance reframe text yet again.

But digital formats also strip certain rituals. A file lacks weight and scent. Discoverability rests on algorithms instead of bookstore displays. The cover becomes a thumbnail on a glowing shelf. Those changes matter because reading is more than decoding sentences — context and habit shape comprehension and pleasure.

So — what actually makes a book a book?

If you reduce a book to only what conveys meaning, then words alone could qualify any medium: scroll, codex, PDF, or narrated audio. But the fuller answer lives in the relationship between form and reception. The physical parts — paper, ink, binding — shaped how authors wrote, how readers navigated, and how societies valued information. They created rituals and economies around books. The digital shift alters those rituals and economies but doesn’t magically change the fact that a sequence of words can transport someone elsewhere.

Think of it like music: playing a record on a turntable and streaming the same album on your phone both let you hear the same songs, but the experiences differ. For many people, the difference matters. For others, access and convenience do.

A small, open-ended verdict

The book we love is both object and vessel. Its identity grew from technological tweaks — paper factories, oil inks, cast type, flexible spines — and from cultural practices like reading aloud, indexing, and collecting. As we slide into a future where words live comfortably on a screen, the old and the new will coexist. Some readers will keep treasuring spines and smells; others will prefer the invisible library in their pocket. Either way, the text keeps doing its work. What changes is how the world carries, sells, and touches that work on the way to a reader’s eyes.

Which matters more to you: the ritual of holding a book, or the freedom of carrying thousands in a device?