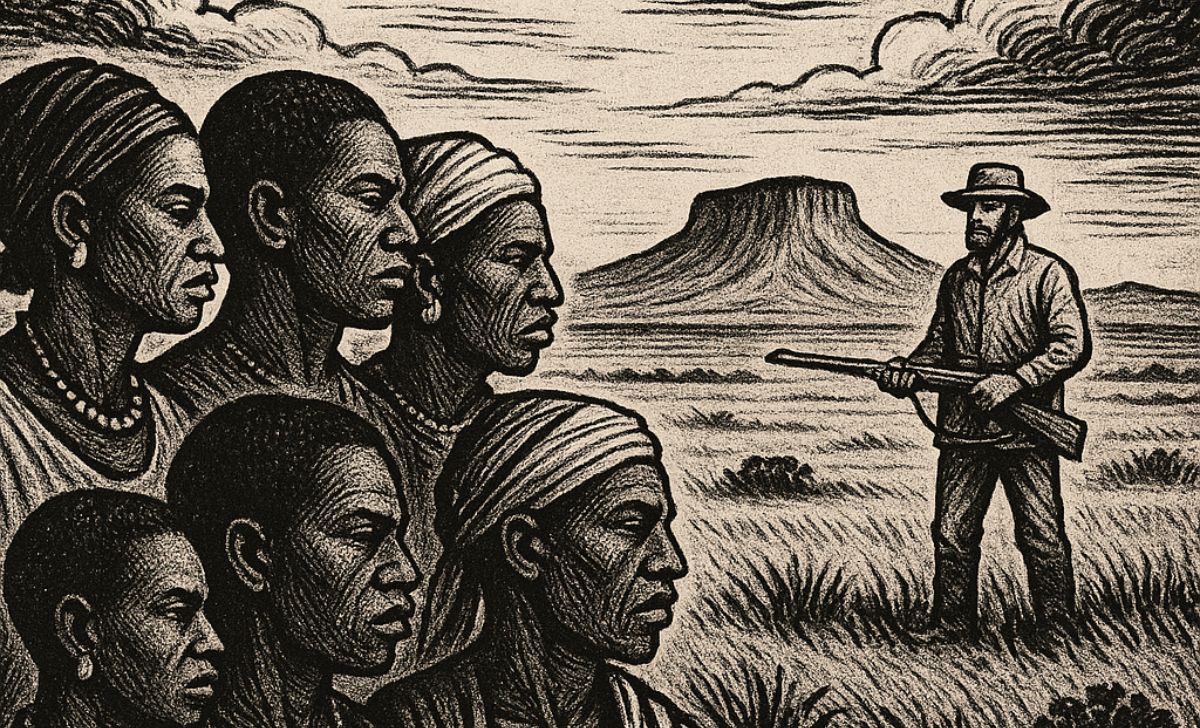

For centuries, the history of South Africa was shaped by myths, colonial narratives, and political propaganda. Among these was The Empty Land Myth, a narrative fostered by European colonists to justify the violent seizure of Indigenous land and the eventual institutionalization of racist policies like apartheid. While cloaked in the language of civilization and progress, this myth was a strategic tool used to erase centuries of African presence and agency in Southern Africa, enabling one of the most aggressive land dispossessions in world history.

European Colonization and the Genesis of the Myth

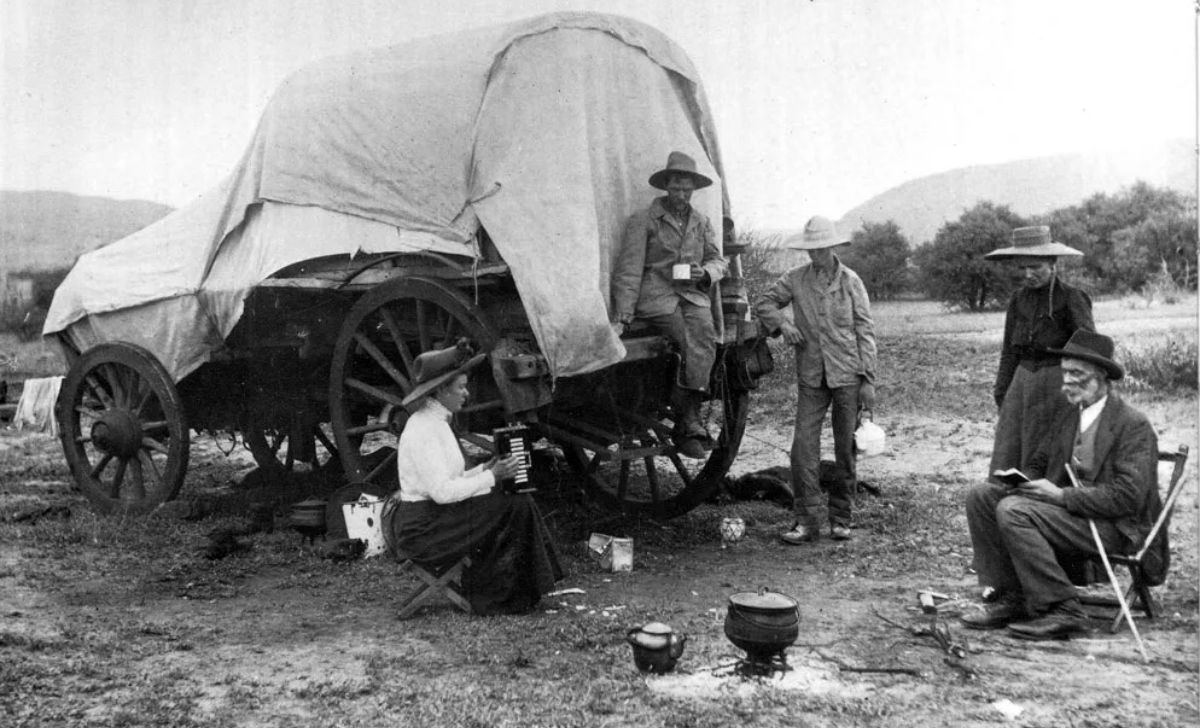

The colonization of South Africa began in the mid-1600s with the arrival of Dutch settlers, who were later joined and eventually displaced by the British. As competition for territory and resources mounted, both colonial powers sought to justify their actions not only to themselves but also to international audiences and future generations. In their quest for legitimacy, they created the narrative that vast expanses of South Africa were virtually uninhabited—so-called “empty land” waiting to be civilized.

This myth was no mere accident. It was a carefully orchestrated campaign, evidenced by letters, travelogues, and maps from Dutch and British administrators, missionaries, and soldiers. Each of these records omitted, minimized, or outright denied the presence of Indigenous peoples, painting a picture of a vast, ownerless expanse.

The Three Pillars of the Empty Land Theory

The Empty Land Theory was founded on three central arguments, each as deceitful as the last:

- No Established Communities or Agriculture

European writers asserted that most of the land being settled lacked established communities or evidence of agricultural development. This was outright false—Bantu-speaking peoples and other Indigenous South Africans had long established intricate social structures, settlements, and food production systems adapted to the region’s environment. - Simultaneous African and European Arrival

Colonizers claimed that African communities in the region arrived at the same time as Europeans, attempting to weaken Indigenous claims to ancestral land. This too was untrue by centuries or even millennia; archaeological and oral histories confirm a deep-rooted Indigenous presence across South Africa long before any European arrived. - Previous Displacement as Justification

Finally, colonists argued that African settlers had themselves displaced earlier inhabitants, so Europeans were within their rights to remove whoever they found living there. This logic was used to rationalize further violence and dispossession and to absolve European powers of guilt.

Indigenous Land Practice vs. European Ownership

The European concept of land ownership—where land is individually owned, bought, and sold—differed sharply from the Indigenous practices of South Africa. Among many Indigenous communities, land belonged to families, clans, or entire groups, not individuals. Furthermore, the emphasis was often on the right to use the land (for grazing, growing, foraging) rather than to own it outright.

Leaders would distribute usage rights depending on the season, water availability, and the group’s needs. Even those communities with permanent settlements saw land as a collective resource rather than private property. These practices were misinterpreted—willfully or not—by colonizers, who dismissed any land without visible fences, deeds, or extensive European-style agriculture as “empty” and thus available for reallocation.

Codification of Injustice: The Glen Grey Act

In 1894, as European control solidified in southern Africa, the Cape Parliament passed the Glen Grey Act. This law:

- Made it almost impossible for Black South Africans to own land.

- Broke apart collective tribal land systems.

- Created a class of landless African laborers, completely dependent on colonists.

The official rationale behind the Glen Grey Act and similar policies called into question the so-called “savagery” and “backwardness” of the local populations, arguing that they lacked the capacity for modern landholding and governance. This paternalistic attitude wasn’t unique to South Africa—it was a recurring theme in colonial regimes on all continents.

The Broader Colonial Playbook: Global Applications of the Myth

The invention and deployment of myths like the Empty Land Theory were not limited to South Africa:

- Australia: The Terra Nullius concept declared the continent “empty,” denying thousands of years of Aboriginal history.

- Canada and the United States: The doctrine of discovery and the principle of Manifest Destiny enabled violent expansion and settler colonialism, similarly denying Indigenous sovereignties.

By consistently portraying Indigenous people as non-existent, transient, or unworthy of land rights, colonizers manufactured the moral and legal space for their own claims. This narrative not only facilitated dispossession but also laid the groundwork for ongoing systemic discrimination.

Consequences: Racism, Segregation, and Apartheid

Stripped of land, the Indigenous population of South Africa became subsistence laborers and miners on white-owned property. They were forced to:

- Work as migrant laborers under harsh conditions.

- Live in racially segregated districts, with severe restrictions on movement and opportunity.

- Accept the loss of traditional ways of life, culture, and autonomy.

The policies grew ever harsher, culminating in the apartheid system. Under apartheid:

- African South Africans lost the right to vote.

- Education was redesigned to emphasize subservience to white authorities.

- Racial segregation reached into every facet of public and private life, rigorously enforced by the state.

Throughout, the Empty Land Myth was cited to justify these inequities: if African people had no legitimate, ancestral claim to the land, what harm was done by their dispossession?

South African Resistance and the Challenge to Colonial History

Despite relentless oppression, South Africans resisted. Movements for freedom took many forms:

- Community organizing and political mobilization.

- Armed resistance and underground movements.

- International campaigns for justice and sanctions against apartheid.

From the late 20th century onward, South African scholars, activists, and teachers worked to correct the deceitful colonial record. Drawing on archaeology, oral tradition, and painstaking archival research, they began to reassert the truth of deep and continuous Indigenous presence in Southern Africa.

By the 1980s and 1990s, as apartheid fell, these efforts bore fruit. South African school curricula began to embrace a fuller, more accurate account of the region’s history—one that acknowledged both the horrors of colonialism and the resilience of Indigenous communities.

The Enduring Legacy of the Empty Land Myth

Although the legal scaffolding of the Empty Land Theory has long since crumbled, its effects endure. Modern South Africa remains marked by:

- Unequal land distribution rooted in colonial and apartheid theft.

- Ongoing debates over land restitution and reparations.

- Persistent stereotypes and racial dynamics initiated by colonial mythmaking.

The work of undoing the damage wrought by this narrative is ongoing. It requires not only legal and political redress but also a fundamental shift in how the past is remembered, taught, and understood.