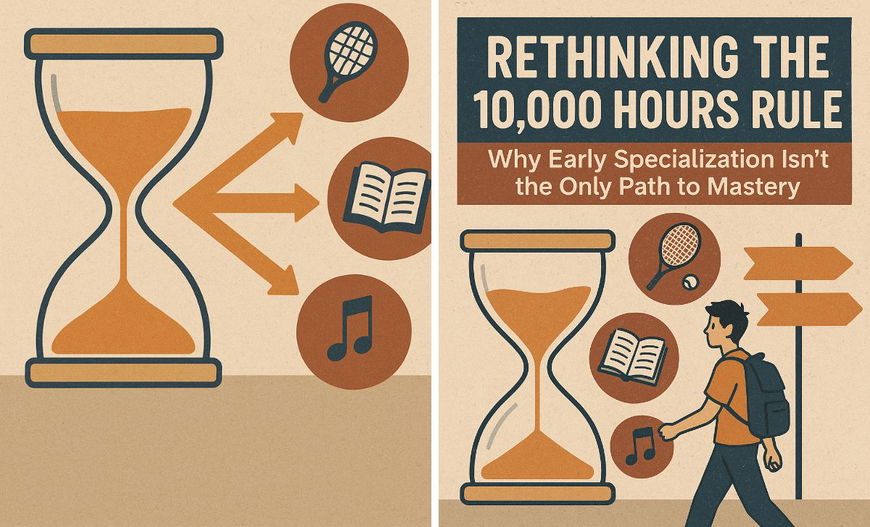

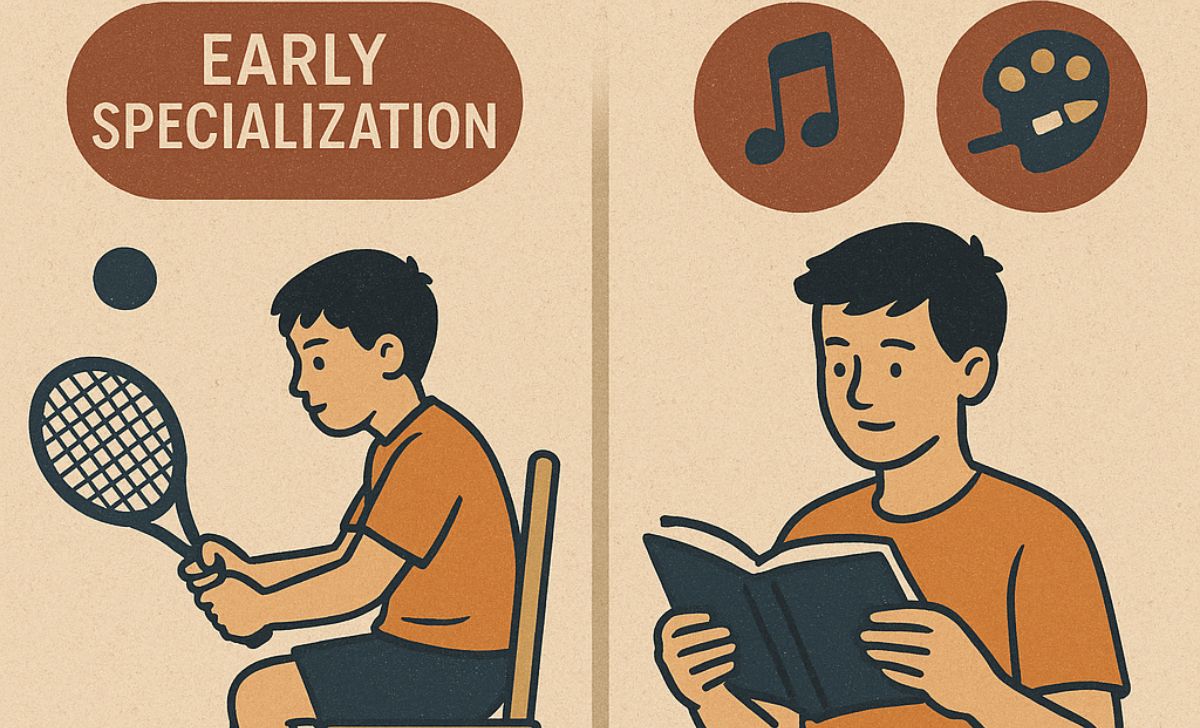

The popular notion that becoming great at anything requires 10,000 hours of focused practice has captivated many minds. This idea, often called the “10,000 hours rule,” has inspired people to start early and dedicate countless hours to their craft, assuming this is the key to elite performance. Tiger Woods’ early introduction to golf and his remarkable rise to the sport’s pinnacle is frequently cited as the quintessential example. Similarly, the Polgar sisters’ rigorous chess training from an early age supports this thinking. But is this tidy narrative the universal truth? As we delve deeper, a different, more nuanced story emerges—one that challenges the inevitability of early specialization and opens possibilities for diverse paths to success.

The Myth of Mandatory Early Specialization

At first glance, studies on elite athletes seem to support the 10,000 hours rule—they spend more time in deliberate practice than their less successful peers. Yet, when we scrutinize the developmental patterns of future elite athletes, a surprising picture emerges. Rather than specializing early, many pass through a “sampling period,” where they engage in a broad range of physical activities. This exploratory phase allows them to develop a wide array of general skills before honing in on one specialty. Intriguingly, delayed specialization often corresponds with higher peak achievement, contradicting the idea that early, singular focus is essential to mastery.

This pattern is not limited to sports—musicians display similar trajectories. Exceptional musicians often do not increase their deliberate practice hours over their peers until they begin learning a third instrument. Even prodigies we associate with early genius, like cellist Yo-Yo Ma, had diverse explorations before intensive specialization later on.

Iconic Examples Defying Early Specialization Narratives

Exploring the backgrounds of notable individuals reveals even more variability in the paths to excellence:

- Duke Ellington avoided traditional music lessons as a child, instead focusing on baseball, painting, and drawing.

- Mariam Mirzakhani, the first and only woman to win the prestigious Fields Medal in mathematics, dreamed of becoming a novelist as a young girl and was not initially drawn to math.

- Vincent van Gogh pursued five different careers before seriously engaging with art in his late twenties.

- Claude Shannon, the father of modern digital computing, stumbled upon his breakthrough idea in a philosophy class taken as a university requirement.

- Frances Hesselbein began her professional career at 54 and eventually became the CEO of the Girl Scouts.

These stories underscore the diversity of successful learning journeys and challenge the rigid expectation of early intense focused practice.

The Case of Roger Federer: A Multi-Sport Journey

Roger Federer, one of the greatest tennis players of all time, also illustrates this less linear route. Before settling on tennis, he dabbled in tennis, skiing, wrestling, handball, volleyball, soccer, badminton, and skateboarding. His mother, a tennis coach, initially refrained from coaching him due to his unorthodox manner of returning balls. Federer’s journey was anything but a straightforward 10,000 hours in tennis from infancy. Yet, he ultimately became a tennis legend, mirroring the fame of Tiger Woods but through a markedly different developmental path.

Golf and Chess: Models of “Kind” Learning Environments

Part of what makes Tiger Woods’ story so compelling—and apparently so clean—is the nature of golf as a “kind learning environment,” a term coined by psychologist Robin Hogarth. In such environments, the goals and rules are clear and unchanging, and feedback is immediate and accurate. Chess is another prime example. These conditions make early and intense specialization particularly effective.

But life and many fields we engage with are often not this straightforward. They operate within “wicked” learning environments that lack clear goals or rules, where feedback can be delayed or misleading. This complexity characterizes much of the modern world and questions the universal applicability of early specialization as a formula for success.

Learning in a Wicked World: The Value of Diverse Experiences

In less predictable, wicked learning environments, meandering between interests, exploring broadly, and maintaining a wide perspective can be advantageous. Though such paths might appear as zigzagging or even falling behind, they build a broad base of skills and knowledge. Research into innovation reflects this: the most impactful inventions often emerge from the cross-pollination of many fields, pioneered by individuals working across diverse technology domains.

Junpei Yokoi, a Japanese innovator behind Nintendo’s Game Boy, exemplifies this. Yokoi, who didn’t excel in electronics exams and started as a machine maintenance worker, combined ideas from calculators and credit cards to revolutionize handheld gaming. His path was not one of early specialization but one enriched by diverse experiences.

Encouraging Both the Frog and the Bird

The eminent physicist and mathematician Freeman Dyson metaphorically described the need for diverse types of thinkers in a healthy intellectual ecosystem. Frogs dig deep into details, while birds soar above, integrating diverse knowledge. The problem, Dyson observed, is that society overwhelmingly pressures everyone to become frogs—specialists deeply immersed in details. Yet, in a wicked world demanding flexibility and innovation, birds who see broader connections are equally vital.

Conclusion: Embracing Multiple Paths to Success

The story of 10,000 hours and early specialization holds truth in specific contexts like golf or chess but does not universally apply to all fields or individuals. Diverse experiences, late starts, and broad exploration play significant roles in the success of many outstanding people across domains. Instead of strictly incentivizing early specialization, societies and individuals should celebrate multiple paths to mastery, recognizing the unique journeys that shape different innovators, artists, and leaders.

This broader understanding allows room for flourishing in a complex, wicked world—one that values not just deep focus but also the insights gained through variety, adaptability, and integration.