Most Famous Mythology Characters With Multiple Heads: Step into the mesmerizing realm of mythology, where extraordinary beings challenge the limits of imagination. Within these ancient tales lie enigmatic figures with a peculiar and captivating trait: multiple heads. From the legendary Hydra to the enigmatic Brahma with four faces, these iconic characters have bewitched cultures across the globe for millennia. Their stories are rich with symbolism and complexity, reflecting the human fascination with duality, power, and the enigmatic nature of existence itself. Join us as we delve into the enthralling narratives of the most famous mythology characters with multiple heads, exploring the profound meanings they hold and the eternal impact they have left on the fabric of folklore.

Most Famous Mythology Characters With Multiple Heads

Ravana (Hindu mythology)

He is most well-known as the primary antagonist in the Hindu epic Ramayana, where he is depicted as a powerful king of Lanka (now known as Sri Lanka). Ravana is renowned for his intellectual prowess, his mastery over the Vedas and astrology, and his ten heads. The ten heads of Ravana are often considered to represent his knowledge of the six shastras and the four Vedas, making him a scholar par excellence. Each of these heads is said to have been engrossed in meditation and committed to austerities, making him mighty, knowledgeable, and a devotee of Lord Shiva.

One interpretation states that the ten heads stand for ten negative emotions or qualities, namely Kama (lust), Krodha (anger), Moha (delusion), Lobha (greed), Mada (pride), Maatsarya (envy), Manas (mind), Buddhi (intellect), Chitta (will), and Ahamkara (ego). These are, in essence, the ten facets of human life that lead one to live a life steeped in materialism and take one away from spirituality.

Ravana’s multi-headedness, therefore, is a key characteristic that marks him as a unique figure in world mythology. His story serves as a lesson about the dangers of ego, lust, and unrestrained ambition. Despite his knowledge and power, Ravana’s downfall was brought about by his inability to control these negative aspects. His tale remains an enduring mythological narrative that offers profound insights into human nature and the struggle between good and evil.

Hydra (Greek mythology)

In Greek mythology, the Hydra is one of the most fearsome and well-known monsters. It is a gigantic serpent-like water monster with multiple heads, that was said to dwell in the lake of Lerna in the Argolid. The Hydra is most famous for its role in one of the Twelve Labours of Heracles (also known as Hercules in Roman mythology).

The Hydra’s most distinctive characteristic was its multiple heads. It is commonly depicted with nine heads, although the number varies depending on different sources, with some suggesting that it had as many as a hundred. The most terrifying aspect about the Hydra’s heads, however, was not their number but their regenerative property – if one of the Hydra’s heads was cut off, it would quickly grow back, often as two heads replacing the one lost. This made the creature nearly impossible to kill, and it terrorized the people of Lerna and the surrounding regions.

The myth of the Hydra’s defeat is a cornerstone in the tales of Heracles. The second of his Twelve Labours set by King Eurystheus was to slay the Hydra. After realizing that he could not defeat the Hydra by simply beheading it due to its regenerative ability, Heracles called on his nephew Iolaus for help. Every time Heracles cut off one of the Hydra’s heads, Iolaus would use a torch to cauterize the wound, preventing new heads from growing back. Once all the heads were removed, Heracles dipped his arrows in the Hydra’s poisonous blood, making his weapons deadly.

Yamata no Orochi (Japanese mythology)

In Japanese mythology, Yamata no Orochi stands out as a prominent multi-headed monster. This monstrous serpent is a significant character in the ancient Kojiki text, Japan’s oldest existing chronicle, compiled in the 8th century AD. Yamata no Orochi, often translated as the “Eight-Forked Serpent,” is depicted as a terrifying dragon or serpent-like creature with eight heads and eight tails. This enormous beast was of such a size that it stretched over eight valleys and eight hills, and its body was covered in moss, trees, and other vegetation.

Yamata no Orochi is most famous for its encounter with the storm god Susanoo. According to the mythology, the monster had been terrorizing a local couple, eating one of their daughters each year for seven years. When Susanoo came upon them, they were about to sacrifice their eighth and final daughter, Princess Kushinada.

In return for her hand in marriage, Susanoo agreed to slay the beast. He set up eight vats of sake (a type of Japanese rice wine), one for each head of the monster. When Yamata no Orochi arrived, it plunged each of its eight heads into a vat, drinking the sake and becoming intoxicated. Susanoo then took this opportunity to defeat the monster, cutting off each of its heads and tails. Within the tail of the beast, Susanoo discovered a magnificent sword, which he named Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi. This sword later became one of the three Imperial Regalia of Japan, symbolizing the legitimacy of the Japanese emperor’s rule.

Brahma (Hindu mythology)

Brahma is a significant deity in Hindu mythology, recognized as the creator of the universe. He is one of the Trimurti, or the holy trinity of Hindu gods, which includes Brahma (the creator), Vishnu (the preserver), and Shiva (the destroyer).

Unlike many other deities in Hindu mythology, Brahma is depicted with multiple heads, typically four, but sometimes shown with more in certain accounts. Each of these heads is meant to symbolize a different aspect of his all-encompassing knowledge. The four heads are also thought to represent the four Vedas (Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda, and Atharvaveda), the primary scriptures in Hindu religion. Additionally, they are sometimes said to represent the four Yugas (eras) in Hindu cosmology, namely Satya Yuga, Treta Yuga, Dvapara Yuga, and Kali Yuga.

Despite his role as the creator, Brahma is not widely worshipped in contemporary Hinduism. This is often attributed to a curse by the sage Bhrigu or a punishment by Shiva due to a mythological incident. Regardless, he remains an integral part of Hindu cosmology, symbolizing the aspect of creation in the cycle of birth, preservation, and destruction. His four heads remind us of the vastness of his knowledge and the expanse of the universe he created.

Hecatoncheires (Greek mythology)

The Hecatoncheires were the offspring of Gaia (Earth) and Uranus (Sky). Disturbed by their monstrous appearance, Uranus cast them into Tartarus, the deep abyss where the Titans were also imprisoned. They were eventually freed by Zeus, and in gratitude, they aided him in the epic battle against the Titans, known as the Titanomachy. The Hecatoncheires used their hundred hands to hurl massive boulders, creating a storm of stones against the Titans, leading to the victory of Zeus and his siblings. After the Titanomachy, they served as the guards of Tartarus, keeping the defeated Titans in check.

The Hecatoncheires symbolize an uncontrollable and overwhelming force, showcasing the power of unity in their shared might against formidable opponents. Despite their terrifying appearance, they played a crucial role in establishing the reign of the Olympian gods in Greek mythology.

Kaliya (Hindu mythology)

In Hindu mythology, Kaliya is a memorable multi-headed serpent or Naga. This creature is best known from the myth involving the Hindu deity Krishna during his boyhood in Vrindavan, a tale beloved in Indian tradition and art. Kaliya, the serpent king, possessed numerous heads, typically five, but depicted with more in certain illustrations. Each head was venomous, making Kaliya a potent and deadly creature. This venom had poisoned the waters of the River Yamuna, making it uninhabitable for other beings.

Krishna, as a young cowherd boy, challenged the fearsome serpent to battle after witnessing the suffering of the flora, fauna, and his fellow villagers. He jumped into the toxic river and danced on the many hoods of Kaliya in what is often referred to as Kaliya Mardan or the subduing of Kaliya. After a fierce battle, Krishna finally overpowered Kaliya. Recognizing Krishna’s divine power, Kaliya begged for mercy. Krishna granted him forgiveness on the condition that he would leave the River Yamuna and stop tormenting its inhabitants.

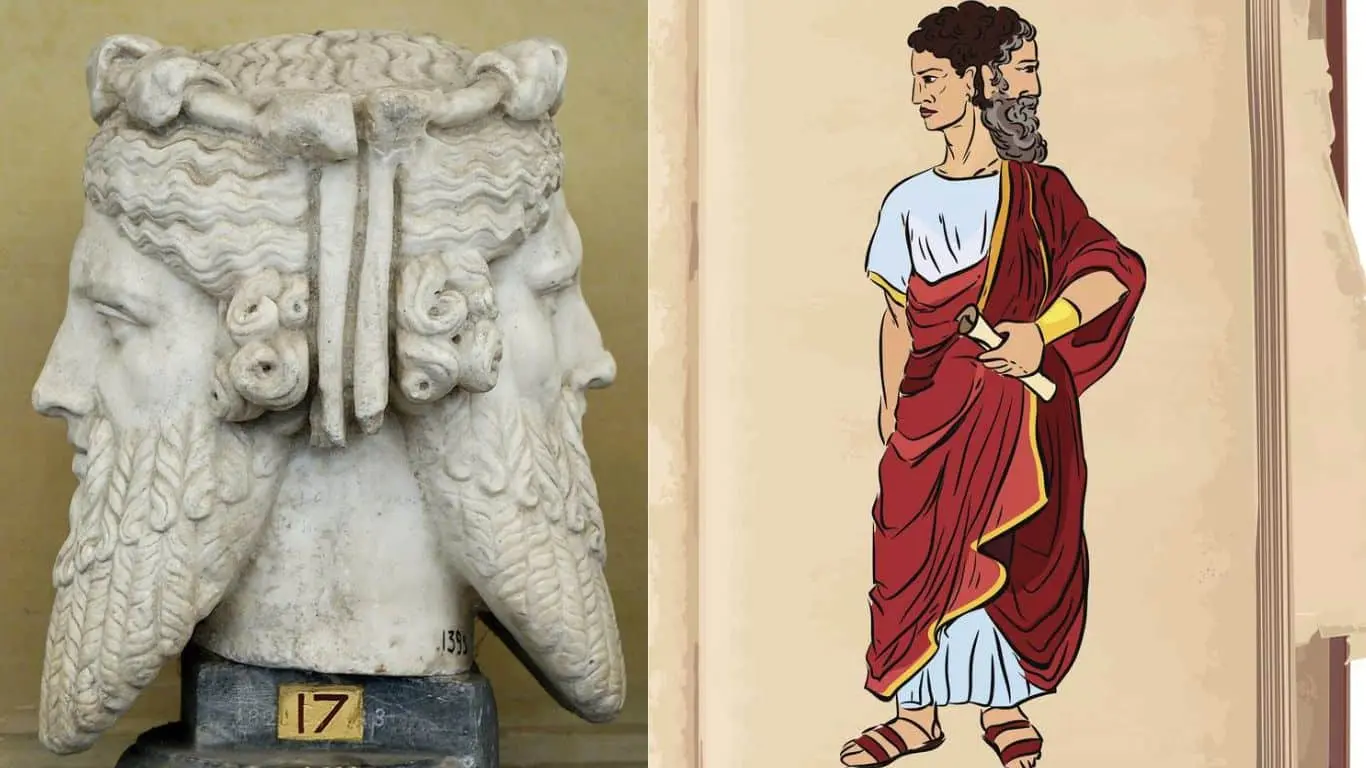

Janus (Roman mythology)

Janus is considered the god of passages, representing the duality of beginnings and endings, the past and the future, and the transitions between them. As the god of doorways and gates, he presided over the opening and closing of doors, both literal and metaphorical. This symbolism made him an important figure in rituals and ceremonies, particularly those related to new beginnings, such as the Roman New Year.

The two faces of Janus signify his ability to look in two directions simultaneously. One face looks back into the past, while the other looks forward into the future. This duality grants him the power of foresight and insight, as well as the ability to guard and guide people through transitions and changes. Janus also played a role in various religious and social contexts. He was invoked at the beginning of important events, such as marriages and military campaigns, to seek his blessings and guidance. Temples dedicated to Janus, known as Jani, were built in Rome, and the gates of these temples were left open during times of war and closed during times of peace.

Janus is a symbolic representation of the complex nature of time and the cyclical nature of life. His dual-faced depiction embodies the concept of transitions and the importance of reflecting on the past while looking ahead to the future. Janus serves as a reminder of the constant change and flow of life, and the need to embrace both beginnings and endings with wisdom and foresight.

Also Read: Saraswati | Hindu Goddess of Wisdom