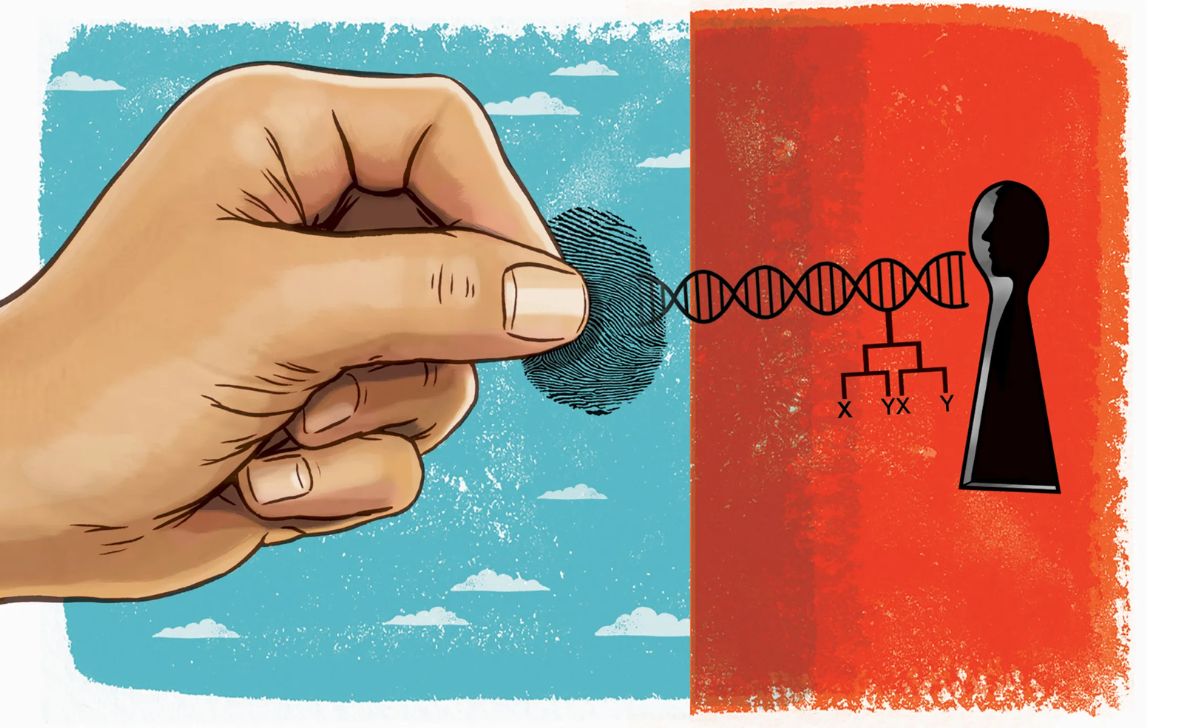

Is it ethical to allow humans to control genetic modification? This question has become one of the most pressing moral debates of our time. As science advances at a breathtaking pace, technologies like preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and gene-editing tools such as CRISPR give us the power to shape human life before it even begins. What once belonged to the realm of science fiction is now a real possibility: choosing which traits our children will have—or won’t have.

While this opens the door to preventing serious genetic diseases, it also raises unsettling questions about where the boundaries should lie. Are we safeguarding future generations—or crossing a line by trying to design them?

The Promise and Power of Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) is a process in which embryos created via in vitro fertilization (IVF) are screened for genetic conditions before implantation. Only embryos that pass the genetic criteria chosen by the parents are then transferred to the uterus.

PGD was originally developed as a way to prevent serious inherited illnesses like cystic fibrosis, Tay-Sachs disease, and Huntington’s disease. For many families, this has been life-changing—offering the chance to have healthy biological children without passing on life-threatening conditions.

However, as the technology has advanced, its use has expanded beyond disease prevention. Some prospective parents now consider using PGD to select for non-medical traits, such as sex, eye color, or in rare cases, traits like deafness. This pushes PGD into ethically murkier territory—transforming it from a tool of disease prevention into a tool of genetic selection.

The Case of Andre and Leslie: Choosing Deafness

Andre and Leslie’s situation is unusual but deeply thought-provoking. As a deaf couple, they live within and value Deaf culture, which includes its own language (American Sign Language, or ASL), rich traditions, and close-knit community bonds. They worry that raising a hearing child might create cultural and communication barriers within their family.

They are considering using PGD to ensure their child is also deaf. Yet they feel uneasy about having such profound control over their child’s future. This reveals the core ethical tension:

- Should parents shape their child’s genetic traits based on what they believe will give the child the best life?

- Or should they accept the natural uncertainty of reproduction, respecting the autonomy of their future child?

To analyze questions like these, many philosophers turn to an ethical concept called the Principle of Procreative Beneficence.

The Principle of Procreative Beneficence

Coined by philosopher Julian Savulescu, the Principle of Procreative Beneficence argues that if prospective parents can choose between possible children, they should select the one expected to have the best chance at the best life.

On the surface, this sounds reasonable—what parent doesn’t want the best for their child? But the principle raises a difficult question:

What counts as the “best life”?

Most hearing people might assume that deafness automatically makes life worse. But that assumption itself is controversial. It reflects what philosopher Elizabeth Barnes calls the “bad difference view” of disability—the belief that being disabled inherently makes life worse.

Barnes challenges this idea with her “mere-difference view”, which suggests that being disabled is not intrinsically bad—it’s simply different. Deaf people, for example, experience music through vibration rather than sound. This doesn’t make their experience lesser, only different. Many difficulties deaf individuals face stem from society’s lack of accessibility, not from deafness itself.

From this perspective, Andre and Leslie’s desire to have a deaf child could be seen not as inflicting harm, but as choosing a different cultural and experiential path.

Culture, Identity, and Parental Responsibility

Philosopher Robert Sparrow argues that parents may be better equipped to raise children who share their culture, because shared experience can foster understanding, trust, and belonging.

Andre and Leslie worry that they might struggle to fully support a hearing child who lives largely outside Deaf culture. They want a child who will grow up immersed in their world, where they can model resilience and pride in their identity.

This argument reframes their choice as one of cultural continuity rather than medical control. And indeed, studies show that children who feel understood and accepted by their parents are more likely to thrive emotionally and socially.

So, following the logic of the Principle of Procreative Beneficence, one could argue that Andre and Leslie might be justified in choosing a deaf child if it maximizes that child’s sense of belonging and wellbeing.

The Slippery Slope of Genetic Selection

However, pushing this logic to its extreme reveals serious problems.

If parents should always choose the child with the “best life,” does that mean selecting against all traits society views as disadvantages? What about skin color, sexual orientation, or gender—traits that can expose people to prejudice and discrimination?

As bioethicist Adrienne Asch warns, this attitude risks sending a harmful message: that lives of people with disabilities—or any marginalized identity—are less worth living. Instead of eliminating people who might face prejudice, she argues, society should focus on eliminating the prejudice itself.

This is a crucial ethical point. The presence of social barriers does not mean that people who encounter them have lives of lesser value. Choosing against certain traits because of existing biases risks reinforcing those very biases.

In other words, if society discriminates against a group, the solution is not to stop people from being born into that group—but to make society more just and inclusive.

Parenting: Acceptance vs. Control

Beyond these philosophical debates lies a more personal question about what parenting is for. Is parenting an act of control, in which parents sculpt their ideal child? Or is it an act of acceptance, in which they embrace the unpredictability of who their child becomes?

Even if genetic technologies could offer the “perfect” child, they can’t guarantee happiness. Life is unpredictable. Health, personality, opportunity, and luck all shape a person’s wellbeing in ways that no genetic screen can fully anticipate.

Some ethicists argue that by trying to control their children’s traits, parents risk treating them like projects or products rather than autonomous individuals. True parenthood, they suggest, means loving your child for who they are, not who you engineered them to be.

This perspective challenges the assumption behind much of genetic modification: that we can, or should, design a “better” human.

The Uncertain Future of Human Genetic Control

Technology like PGD and CRISPR will only become more powerful and accessible. In the near future, it may be possible to not just select embryos but actively edit genes to remove disabilities or enhance desired traits like intelligence, memory, or athleticism.

This raises profound societal questions:

- Who decides which traits are desirable?

- Will genetic enhancement become a luxury for the wealthy, deepening inequality?

- Could “designer babies” erode human diversity, as people select for a narrow set of traits?

These concerns suggest that ethical oversight, public dialogue, and regulation are crucial as humanity moves deeper into genetic engineering. Without them, we risk turning the human gene pool into a marketplace of preferences rather than a shared human legacy.

A Path Forward: Humility and Responsibility

So, is it ethical to allow humans to control genetic modification?

There may be no universal answer—only careful, case-by-case consideration grounded in empathy, humility, and responsibility. Technologies like PGD can alleviate suffering, but they also carry the danger of reducing children to chosen traits rather than cherished individuals.

For Andre and Leslie, the best choice might not lie in controlling genetics, but in preparing to love whichever child they have. Their lived experience in Deaf culture could enrich any child’s life, hearing or deaf. And their willingness to wrestle with this question shows they already possess the most vital trait of all: deep care for their future child’s wellbeing.

Ultimately, the ethics of genetic modification should not be about striving for perfection. They should be about honoring human diversity, respecting autonomy, and building a world where every kind of life is valued.

🌱 Final Thoughts

Humanity now holds the power to shape its own evolution. But power is not the same as wisdom. The question is not just what we can do with genetics, but what we should do—and why.

As we stand at the edge of this new frontier, perhaps the most ethical path is not to master nature, but to learn to coexist with its unpredictability—celebrating every child, not for their genetic traits, but for their humanity.