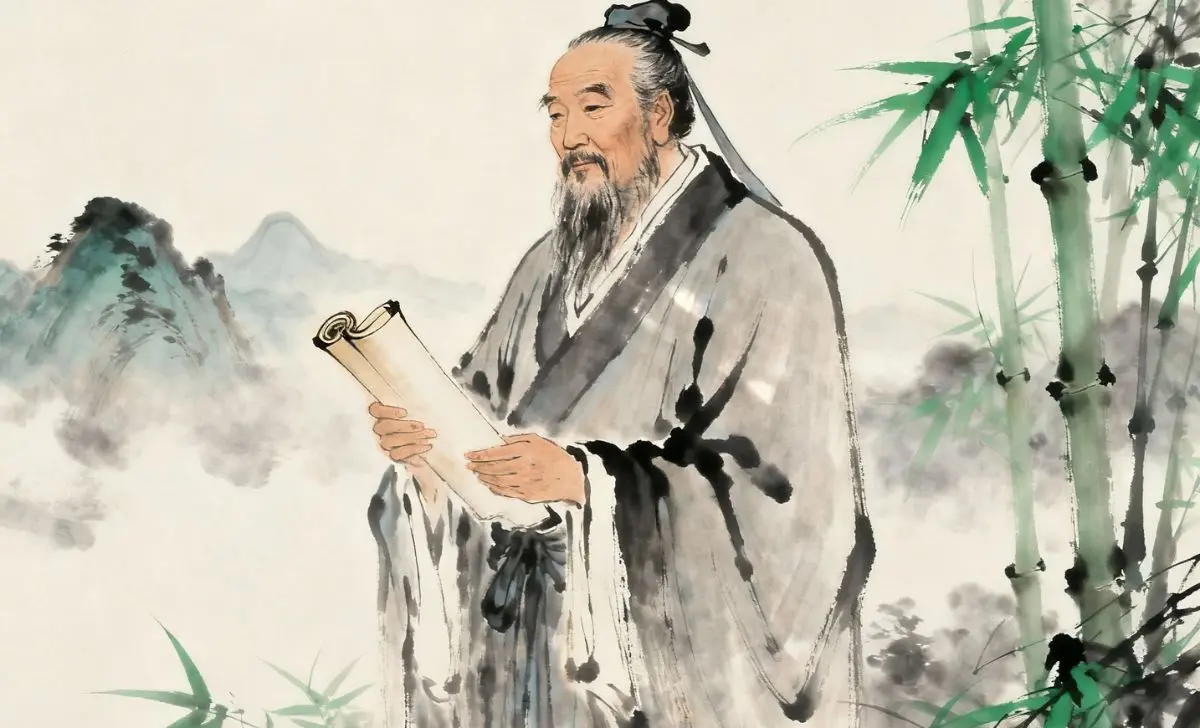

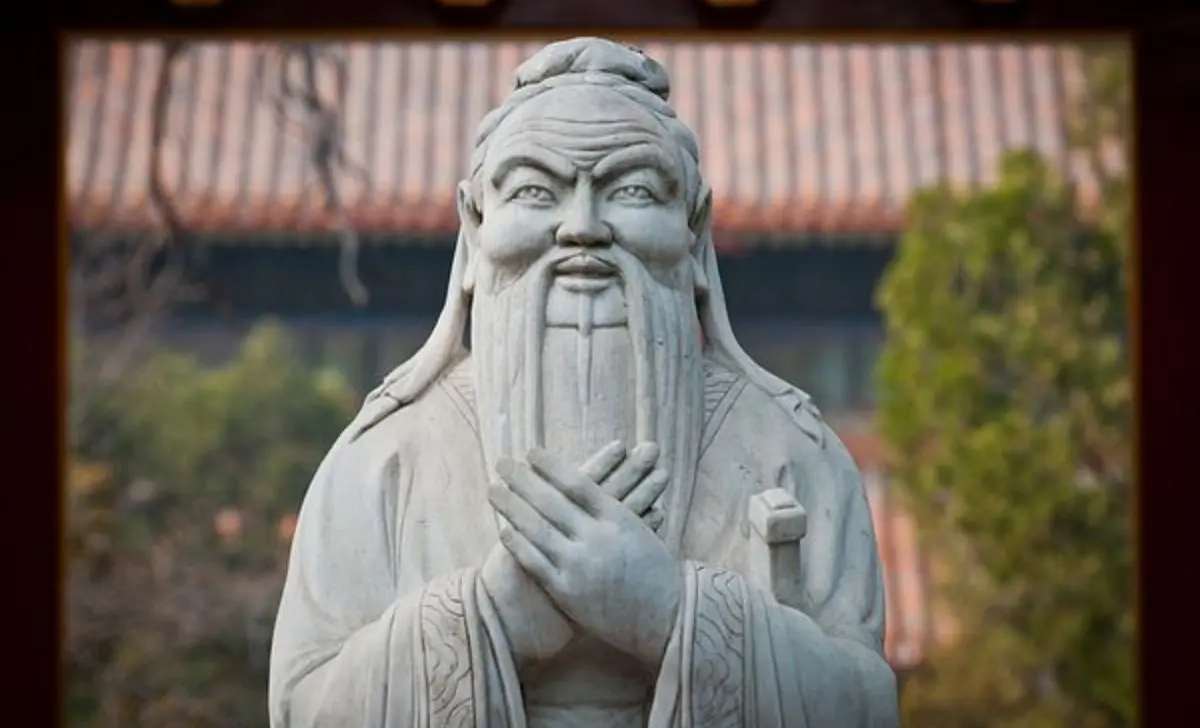

Confucius stands among the greatest philosophers and thinkers in human history. Though countless people recognize his name and know his wisdom endures—often through fabled sayings—few truly appreciate the depth of his character, the turbulent world he navigated, and the global legacy of his thought. Exploring his origins, teachings, and enduring impact reveals why Confucius remains not merely a symbol of Chinese civilization, but a universal guide to ethical life.

The Tumultuous Context of Ancient China

Confucius was born as Kong Qiu (孔丘) in 551 BCE in the state of Lu (now Qufu, Shandong province), during the Spring and Autumn period marked by political fragmentation, warfare, and moral crisis. The child of an aging minor official and a noble family brought low through generations, Confucius lost his father at just three years old, and was raised in poverty by his mother. Despite such adversity, the young Confucius displayed remarkable drive for learning and reverence for ancient traditions.

Education was at the core of his early life. He threw himself into studies—first in everyday schools accessible to the common class—and later, through the rare support of a wealthy friend, delved into the ancient archives of the Zhou dynasty. Confucius believed that “the Six Arts”—ritual, music, archery, charioteering, writing, and mathematics—offered the tools to cultivate an ideal person.

Trials and Early Ambitions

Orphaned and poor, Confucius supported his mother and disabled brother while still a teenager, taking odd jobs such as tending granaries and livestock. He married at age 19, becoming a father a year later, but family responsibilities and the loss of both parents by age 23 deeply shaped his sense of duty and the centrality of mourning rituals and filial piety.

Confucius entered government service in his twenties, gaining a reputation for honesty and competence. He worked his way up from minor roles to overseeing public works and, eventually, as Minister of Crime—one of the top posts in Lu. In these roles, he achieved considerable respect for implementing reforms and steadying the legal system. However, jealousy and political intrigue from entrenched aristocratic families soon forced his resignation.

The Itinerant Philosopher

Exiled from officialdom by power struggles, Confucius spent the next 14 years wandering from state to state, seeking a ruler willing to embody virtue as the basis for just governance. He faced hunger, danger, and repeated disappointment, but remained true to his ethical ideals: government led by moral example, not by force or coercion. During this period, he developed his key teaching: that only a society guided by virtue, rituals (li), and humanity (ren) could achieve lasting harmony.

His faith was unwavering: “Heaven has given me this power—this virtue. What can my enemies do to me?” Even in the face of violence and near-starvation, Confucius retained his conviction that a person devoted to learning and music would find inner joy.

Foundational Concepts and Key Teachings

The Analects and the Heart of Confucian Wisdom

Confucius’s disciples carefully recorded his words and stories. Their efforts culminated in The Analects (Lunyu), a collection of brief, powerful dialogues and aphorisms that form the backbone of Confucian philosophy. These writings emphasize moral cultivation over ritual or knowledge for their own sake: “When you see a worthy person, seek to emulate them; when you see an unworthy person, examine yourself.”

Key principles include:

- Ren (仁): Humanity, benevolence, or “Goodness.” It is the highest virtue—true concern for others and the source of ethical conduct.

- Li (礼): Ritual propriety—rules of behavior in every social interaction, from family to government. Li gives order and beauty to life, while Ren fills it with living compassion.

- Xiao (孝): Filial piety—the respect, care, and loyalty owed to one’s parents and ancestors. Confucius saw this as the root of all other virtues.

- Yi (义): Righteousness—doing what is right for its own sake, not for personal gain. It reflects acting with justice and honor, even when inconvenient.

The Silver Rule

Confucius’s ethical vision is often summed up by the Silver Rule, a negative form of the Golden Rule: “Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself.” This call for empathy and reciprocity remains relevant worldwide, two and a half millennia later.

Teaching as Vocation

Confucius was China’s first professional teacher, accepting students of all social classes and backgrounds—a revolutionary step in a rigidly hierarchical society. He taught more than 3,000 pupils, of whom some 70–77 became recognized as exemplary disciples. His curriculum included not just intellectual study but the cultivation of character—“learning to be human.”

Confucius famously charged little or no tuition, asking instead for a token gift, so that every learner could have access to education regardless of family or status. He inspired an enduring reverence for learning in Chinese culture, seeing education as the key to personal and societal reform.

Confucius’s Political Philosophy: Leading by Example

In a world ruled largely by violence and intrigue, Confucius advocated for a government led by virtue and ritual rather than brute power. “If the people are led by laws and kept in line by punishments, they will try to avoid punishment, but have no sense of shame. If they are led by morality and kept in line by the rules of propriety, they will have a sense of shame and become good.” He believed rulers should gain the people’s respect and spontaneous obedience through personal example, not through threats or rewards. In Confucius’s ideal, the ruler is “the wind, and the people are grass: when the wind blows, the grass bends.”

His insistence that government should serve the people, and not the other way around, influenced Chinese theory of legitimate rule for centuries, underpinning the doctrine of the “Mandate of Heaven.” The ruler’s virtue was believed to justify his authority.

Ritual, Poetry, and Music

Confucius saw art and ritual not just as social decoration, but as central tools for personal growth and societal harmony. The Book of Odes—ancient Chinese poems—taught his disciples how to express and regulate emotions, while music and the correct observance of rituals could shape the character and bring inner and communal peace. “Music brings about harmony; rites ensure order,” he asserted.

Family as the Core of Ethics

The family for Confucius was not only a private sphere, but the foundation of all virtue, and the blueprint for society and government. Love and respect learned within the family—especially through filial piety—formed the ethical groundwork for relationships, leadership, and citizenship. He even argued that, at times, family loyalty superseded duty to the state—a radical view that stressed compassion and mutual responsibility over blind adherence to law.

Influence and Legacy

The Spread of Confucianism

Confucianism flourished after Confucius’s death, with disciples promoting his texts throughout China, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. By the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), Confucian texts became required study for anyone seeking government office, a tradition that endured for nearly two millennia.

The primary texts of the Confucian canon—the “Five Classics” (attributed to Confucius’s editing) and the “Four Books” (highlighting The Analects)—became the basis for civil and ethical education across East Asia.

The School and Lineage

Confucius’s direct descendants were repeatedly honored with noble titles in China, and his birthplace Qufu became a major pilgrimage site. Throughout the centuries, emperors, scholars, and ordinary people have paid homage to him and his teachings—in both elaborate temple rituals and annual festivals.

Major Successors and Contemporaries

Among his chief successors, Mencius (Mengzi) asserted that human nature was innately good, while Xunzi stressed the need for conscious effort to overcome selfish impulses. Their debates expanded Confucian philosophy, shaping the Chinese discourse on ethics, human nature, government, and the role of education.

During the Song dynasty, Neo-Confucianism—spearheaded by thinkers like Zhu Xi—renewed and reformulated Confucian thought, emphasizing metaphysics and self-cultivation, and intertwining elements from Buddhism and Daoism.

Confucius in the Modern World

In the 20th century, Confucianism saw both criticism and revival. During China’s Cultural Revolution, Confucian practices were denounced as relics of feudalism; yet in the later 20th and 21st centuries, his legacy reclaimed an honored role in Chinese society and across East Asia. “Teacher’s Day,” celebrating Confucius’s birthday, is a major public holiday in Taiwan and still honored throughout the region.

His ideas continue to resonate. Not only have they defined much of East Asian civilization, but they have influenced global conversations on education, leadership, and morality, inspiring thinkers from Voltaire to Jefferson.

Conclusion: The Everlasting Relevance of Confucius’s Wisdom

Behind the well-worn aphorisms is the story of a man who strove for justice amid chaos, whose emphasis on humanity, ritual, merit, and the power of education transformed society from the inside out. His teachings about “not doing unto others what you would not want done to yourself,” the primacy of family, and the necessity of leading by ethical example offer guidance for individuals and nations alike—guidance as relevant today as it was 2,500 years ago.

Confucius believed that “to learn and never tire of learning is wisdom.” It is in this spirit of perpetual curiosity and compassion that his vision continues to inspire humanity.