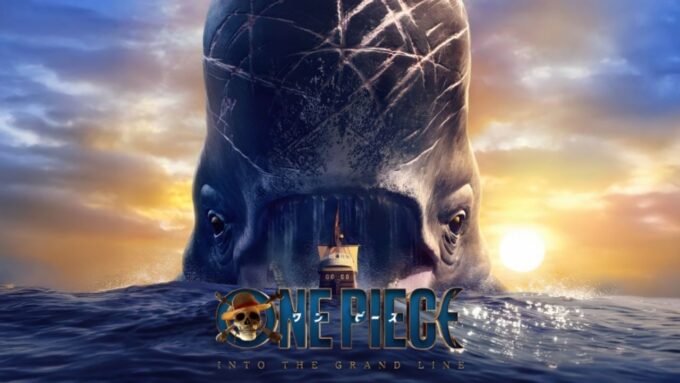

The book begins with a stark image: a mother and her son trudging across an unforgiving desert, their special suits salvaging every drop of moisture from their bodies. Each step is taken without rhythm, careful not to disturb the sands that seem to listen for intruders. Then the silence fractures — the ground hisses, sand surges, and a colossal worm erupts from beneath, a creature as vast as a mountain. This opening is both spectacle and statement, showing how Dune turns desert, spice and power into a living story. Frank Herbert doesn’t use the landscape as mere scenery; he fuses environment, faith, politics, and survival into one interconnected system where humanity must transform or be consumed.

A future without thinking machines — humans become the machines

Herbert imagines a wildly different path for technological progress. After an ancient and devastating conflict with artificial minds, humanity has outlawed machines that act like brains. Instead of turning inward to silicon, people train bodies and minds into new instruments: some become razor-sharp analysts, others become prescient pilots and secretive order-holders. The result reads less like a star-spanning techno-utopia and more like a feudal court where specialists — biological “tools” of a kind — sit at every table.

That creative constraint does more than look unique on the page. It asks: what happens when you remove the easy substitute of computation and force humans to stretch? The answer Herbert gives is uncanny and unsettling: humans convert culture, discipline, and religion into technologies of their own.

Spice and geopolitics — why sand equals power

At the financial and strategic heart of Arrakis sits one commodity — spice, also called melange. It tastes like a legend: rare, intoxicating, and essential. Without it, interstellar travel falters; with it, empires thrive. Because spice grows only on this one desert planet, whoever controls Arrakis controls the universe’s circulation of power.

Herbert stages House Atreides’ arrival on Arrakis as a political chess move — a transfer of stewardship that hides darker designs. The entrenched rulers, the Harkonnens, have blood and cruelty invested in the planet; when Atreides step in, old loyalties and hidden plots destabilize the fragile balance. The story moves quickly from policy memo to uprising, throwing one young man — Paul — into the center of a revolt that becomes much more than a local insurgency.

Think of spice like oil or a modern platform monopoly: it’s both an economic engine and a cultural battering ram. Whoever controls the supply shapes who moves, who lives, and who rules.

A living desert — Herbert’s ecological imagination

Herbert didn’t slap sand on a map and call it a planet. He sketched an ecology: wind funnels and climate bands, niches where tough plants cling, and a system in which every part plays a role in producing spice. The sand itself isn’t inert; it hosts the worms, which are part of a life-cycle that ultimately feeds the planet’s most valuable resource. In Herbert’s hands the desert becomes a character with moods, strategies and a memory of human trespass.

If you’ve ever watched a coastline shaped by tides or seen a forest recover after fire, you’ve seen the kind of slow, systemic intelligence Herbert dramatizes. Arrakis reacts, resists, and rewards those who learn its grammar.

Witches, human calculators and other human “technologies”

Religion and secret orders run through Dune like underground rivers. Paul’s mother, a member of the Bene Gesserit, practices a discipline of body and mind that reads like ritualized psychology — an order that shapes bloodlines and manipulates history in subtle ways. The Mentats, bred and trained to think like living computers, provide razor logic in a world where silicon logic is forbidden.

These groups are not window dressing; they are instruments of social engineering and survival. The Bene Gesserit’s rituals and the Mentats’ computations act as societal scaffolding, replacing machines with human systems of control. The novel shows how ritual, training, and selective breeding can perform the functions that tech ordinarily would.

The Fremen: indigenous knowledge and revolutionary force

At the heart of Arrakis are the Fremen — the planet’s native people. They’ve adapted to the desert utterly: their knowledge of sand, storms, and the monstrous worms makes them custodians of secrets most outsiders can’t imagine. When Paul enters their world, he doesn’t simply learn survival skills; he steps into a culture that centers long-term strategy and ecological reverence.

Herbert presents the Fremen as both the planet’s conscience and its military power. They are at once custodians of place and the seed of a revolution. When outsiders treat Arrakis as a resource to be plundered, the Fremen’s resistance reads as the inevitable clash between extraction and stewardship.

Form that reflects scope — layers of history and myth

Herbert structures the book to feel like a long, uneasy memory. Chapters open with epigraphs lifted from future histories; the novel includes mock appendices and a glossary that make the world feel deep and lived-in. Those devices do more than display world-building; they show how myth, bureaucracy and academic distance will interpret — and sanitize — the violent events unfolding beneath them.

And indeed, the tale is only the opening salvo. Dune launches a saga that stretches across six books and centuries of imagined history. The novel does not merely tell a plot; it proposes a civilization.

Why Dune still matters

Dune survives, not because it gave readers a single great showpiece, but because it braided so many concerns: ecology, power, religion, the politics of scarcity and the lengths to which humans will go when machines no longer shoulder the burden of thought. The spice is a plot engine and a metaphor; the sandworm is spectacle and ecosystem. Paul’s arc — from noble scion to revolutionary figure embedded among the Fremen — tracks a larger question: how do people transform when their survival depends on changing not just tactics, but themselves?

If you approach Dune expecting only desert opera, you’ll miss how Herbert uses environment as policy and faith as technology. Read it as an atlas of consequences: what we value, how we control it, and what we become when scarcity and secrecy shape the center of civilization. The book keeps asking the same hard question: when a whole society learns to improvise in the absence of an easy tool, who will write the rules they live by?